|

|

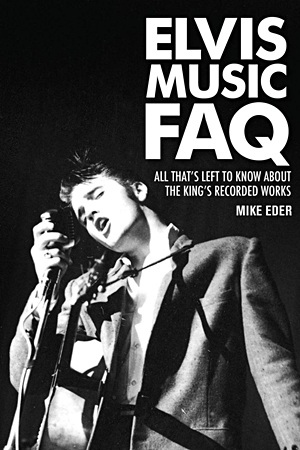

Backbeat Books, USA, 2013, Softcover, 362 pages, Illustrated (b&w), ISBN-13: 978-1617130496 Reviewed by Nigel Patterson, Dec 2013

Eder’s text is thoughtful, continually resonating how carefully he has considered the interaction of Elvis the recording artist and Elvis the performer.

There is plenty to savour throughout the narrative as the author offers an often fresh take on Elvis, his music and tangential issues. Eder’s colourful prose paints a multi-layered canvas – on one level reflecting on Elvis’ recordings in a context of ‘environmental/broader influences’ and on another level taking the reader deep within individual recordings.

For example, Eder regards Hound Dog as the “defining work of (Elvis’) entire career”:

“Hound Dog” breathes the same rarefied air of prestige as “Don’t Be Cruel”. An iconic recording of the first order, there was some truth to the gag when Elvis took to introducing it as the national anthem. it is a magical record, one that grabs the listeners from the first note and doesn’t let go until it’s finished………………Scotty’s multiple solos are increasingly more wild and metallic. The defining work of his entire career, it’s no hyperbole to call this an important part of the evolution of hard-rock guitar. Booming and echoing around the ear canal, D.J.’s drums sound like machine gun fire.

June 8, 1956, Los Angeles. Vol 2 from the outstanding 'Rockin' Rebel' bootleg series

Eder’s thought process on his subject matter also reflects a serious consideration of how Elvis’ recordings changed over time. In considering the musical numbers in Viva Las Vegas, Eder observes:

The slick Red West and Joe Cooper rocker ”If You Think I Don’t Need You” was a solid selection. It lacks some of the daring Elvis might have given it during the fifties or late sixties, but the restraint in this case adds a nice bit of tension. Red thought going for a Ray Charles type of song would yield better results than writing something stereotypically “Elvis”. Elvis in turn seemed to have more fun stretching out than sticking to a more predictable formula.

The author also offers nice insight to the filming of the musical content of Elvis’ third feature film, Jailhouse Rock (and in so doing, comments meaningfully on the visual iconography of Elvis in his films):

Treating Elvis like a creative entity whose input mattered, choreographer Alex Romero didn’t make Presley conform to his vision of how the music would be presented. Instead, he created the dance routines around Elvis’ real style. And with the possible exception of Loving You, none of his other films presented him with such a proper showcase for his music.

Eder also notes the importance of Elvis’ music to socio-cultural changes. On Heartbreak Hotel he writes:

As “Heartbreak Hotel” slowly became a phenomenon, it gave young people something of their own to hold on to.

On Elvis’ changing musical direction in the mid-1950s Eder comments (both insightfully and somewhat contentiously):

“I Was The One” was another leap forward in an unexpected direction. Elvis’ attachment to romantic love songs had not been on public display before, and his use of backing singers (makeshift though they were) was also something new for him. Until now, Elvis had never sounded even close to this self-assured when dealing with a slow beat, nor had he issued a ballad that modern teens could relate to personally. Backed by a good rhythm, and coming across far less country than the slow songs he had cut up until now, it was the prototype of the Elvis “beat ballads” to come over the next several years.

Eder also notes that on I Was the One, Elvis sounds more seasoned vocally than he had at Sun and this helped:

.......his credibility in getting the theme across. Only eighteen months into his career, the growth in Elvis is staggering.

Similarly, in considering Elvis the performer, Eder contends:

Being the expert performer he was, Elvis had the natural instinct and self-taught knowledge to grasp the way his audience would respond to him.

In addressing the malaise that afflicted Elvis’ (largely movie) recordings in the 1960s Eder comments insightfully:

By doing this kind of challenging material [Tomorrow Is A Long Time], Elvis was valiantly fighting against the morass of dead ends his career had become. Because of its sheer quality, “Tomorrow Is A Long Time” is one of the key performances in Presley’s career.

While My Way may be most associated with the iconic recording by Frank Sinatra, Eder observes:

One of Elvis’ strengths was to take songs and make them his own. It would be nearly impossible for anyone else to encroach on Frank Sinatra’s territory, but Elvis completely reinvents the ballad as a statement of purpose. This composition remains fresh to the end, the lyrics being among those Elvis afforded personal meaning to.

While Eder’s chronological consistency in treating Elvis’ music unfortunately wavers back and forth at times, his assessment of how Elvis’ recorded output changed over time, highlighting the personal and extraneous forces which impacted Elvis and affected his studio recordings and live performances, is a strong one. The result is the reader attains a great feel for Elvis and his music as a whole rather than just the relative importance of individual recordings. Both positive and negative influences are well covered with a refreshing honesty sometimes missing in other accounts of Elvis’ career:

1963:

Elvis headed back to Radio Recorders to cut the Fun in Acapulco L.P. It was a poor collection, with “Bossa Nova Baby” being the only good song, and “Guadalajara” the sole authentic representation of Mexican music. Otherwise, it was distressingly bad, coming only three years after the brilliance of the Elvis Is Back! recordings. Elvis sang well enough, but he couldn’t save the album or the movie.

In May, Elvis went to Nashville to record a new studio LP and a few singles. The sessions weren’t completely devoid of the quality issues plaguing the 1961-62 non-soundtrack recordings, but on the whole the results were better than almost anything he had cut since 1960. There was less Latin-style crooning, and even those numbers were more restrained. A lot of rock and roll was cut, and there was even an R&B flavor to some of the masters. Top that with a few remarkably well-sung ballads and you have yourself a fine LP.

Sadly, Colonel Parker didn’t see it the same way, and the music was to be parceled off as soundtrack LP filler, a few singles, and the 1965 Elvis for Everyone compilation.

1970:

The release of “I’ve Lost You” proved two things. The first was that Elvis was staying contemporary, and the second was that this was not necessarily how the masses wanted him.

1976:

Nineteen seventy-six is often agreed as the point where Elvis’ decline really started to affect him. His weight shot to an all-time high, most of it stemming from an unhealthy bloat he attained as his body began to break down. He worked very hard, but the unevenness of the last three years had now reached a point where the bad moments weren’t evenly matched by the good ones. With a total of ten tours, two casino engagements, and two sets of recording sessions this year, one couldn’t complain that Elvis wasn’t prolific. What did rankle was the quality of much of his work, especially onstage.

There has been some criticism of Elvis Music FAQ within the “inner” Elvis world. Yes, Eder’s examination of the Elvis music catalog does stray off on tangential issues including Colonel Parker’s management of Elvis and the presence of ETAs. Not all of the detours are music based.

That the author addresses aspects of Colonel Parker’s management of Elvis is certainly legitimate, given there were various management decisions which restricted Elvis’ ability to regularly record contemporary and quality musical output!

It is also very important to note that Elvis Music FAQ is targeted at both the casual Elvis fan (who are likely to comprise the majority of sales for the book) and not just the hardcore Elvisphile! While some of the latter may question the inclusion of narrative on artists such as Jimmy Ellis (Orion) it should be remembered that, 36 years after his death, Elvis ‘sound-alikes’ and tribute artists are a material element in keeping Elvis and his music alive. In fact, in 2014 they probably do more on an ongoing basis to keep the Elvis song catalog before the public than does Sony Music.

An argument can also be put that by taking these often interesting detours, Eder maintains interest throughout his nearly 400 page journey of Elvis’ music canon. Those expecting a focused analysis of just Elvis’ music will not agree.

In the chapter Come Along With Me, he examines songs ‘discarded’ (not being released by RCA on any regular LP, EP or single), for example Britches; Black Star and Have A Happy; while in Long Lonely Highway he provides a guide to Elvis’ Hollywood Years. Love The Life I Lead is an examination of the most underrated and often ignored year in Elvis' career....1971 while I Can Roll, But I Just Can't Rock looks at 1976, the point where many consider Elvis' decline really started to afect him. Eder’s detour into the world of Elvis tribute artists and sound-a-likes hasn’t pleased some fans (the subject being viewed as extraneous to Elvis’ music), however there will be readers who will find it interesting. To me its value is as a symbol of the influence of Elvis’ music on other people.

Another area where Eder strays tangentially is in assessing Elvis’ films (as against just their musical content). There are too many chapters on Elvis’ film career! Had Eder kept this to one chapter and not several I would have little issue with this particular detour as I believe his thoughtful analysis adds valuable information for the reader to consider. For instance:

Live a Little, Love a Little plays like a daring late-sixties sitcom. The presence of the future second Darrin in Bewitched, Dick Sargent, certainly adds to that impression, but the film is charming in its somewhat distant take on modern love affairs.

With the exception of the numerous chapters about Elvis’ celluloid career, the author’s segue into non-musical issues didn’t greatly affect my overall enjoyment of Elvis Music FAQ. I suspect that for many casual and even some ‘hardcore’ readers, some, but not necessarily all of the detours, will be an interesting side dish which complements the main course of sweet and savoury messages about Elvis’ recordings.

Also, Eder would have been best served by treating the Comeback Special (given its significance in the Elvis music story) in greater detail – while there are references to it throughout the book Eder’s analysis would have been better considered if the chapter (Saved) was greater than 7 pages (in comparison he devotes 11 pages to the Aloha satellite special). Eder does however make a relevant observation:

Though Elvis’ 1968 Singer Presents Elvis television special has rightly been seen as a major turning point, it was not the first step in what has come to be known as his “comeback”. If you go strictly by his non-soundtrack studio recordings, the entire period of 1966-1972 represents Elvis as a mature artist trying to create a new sound for himself.

While the author claims to review every song recorded by Elvis I’m not sure this is actually the case (but I didn’t go hunting to confirm my suspicion). At times the narrative timeline (which starts out as linear) becomes confusing as Eder goes backwards and forwards – retaining a linear progression would have improved the book.

Having said this, Elvis Music FAQ is an entertaining, informative and insightful examination written in an easy flowing writing style. Eder also has a wry sense of humour. For example, I smiled broadly when reading this passage:

Follow That Dream was a somewhat condescending comedy, but as it and Kid Galahad were filmed before the Blue Hawaii clone program began, they are actual movies. They have good actors, interesting scripts, and a few unctuous moments, and, in the case of Kid Galahad, there are even some cool songs.

And after discussing the unfortunate recording of Confidence (in Clambake), Eder observes:

“After that, “How Can You Lose What You Never Had” sounds like a masterpiece. It isn’t extraordinary, but the soulful, country-tinged music is solid. Played either by Jordanaire Hoyt Hawkins or Floyd Cramer, the organ is slick, and Elvis makes an effort to overcome the clumsy words. Reflecting the unfathomable tastes of those who made these decisions, it was snipped from the film.

Many of the chapter titles in Elvis Music FAQ are intriguing and suggestive of issues in both Elvis’ life and career (again symbolising Eder’s analytical approach to his subject). Examples include:

Elvis Music FAQ also features a foreword by Lee Dawson from Elvis Express Radio in the UK.

Verdict: Elvis Music FAQ is an entertaining and informative read. It will satisfy the casual reader with the breadth of its multi-layered coverage and insight, and will be a nice “refresher” for the more ‘hardcore’ fan. Much of the book’s impact and inherent strength is that the author “knows his music” and insightfully addresses broad influences which affected the quality and direction of both Elvis’ studio and live recordings and paints a vivid picture of Elvis as a creative artist often constrained by forces seemingly beyond his control. The book does cover more than just Elvis’ music and in that sense would have benefitted from a more appropriate title.

-Copyright EIN January 2014

EIN Website content © Copyright the Elvis Information Network.

|

|