EIN has chosen a random selection - one from Elvis' classic fifties SUN sessions, a sixties Gospel classic, and a seventies rocker.

If you enjoy these three excerpts than you are surely going to enjoy the whole book. (See Nigel's detailed review here)

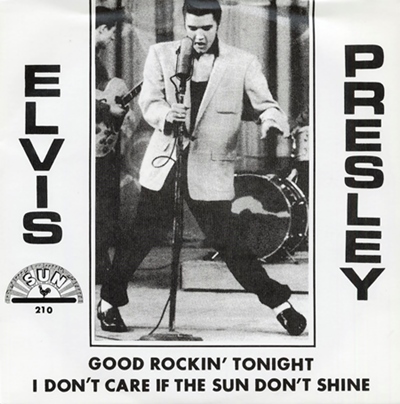

Later sleeve used for BearCat label re-issue

“Good Rockin’ Tonight” - #68

'Elvis, when he played his guitar standing up, he’d just come up on the balls of his feet, and with the big breeches back then—big pants leg—when he’d do that and playing, well the things would start shaking. That’s what the little girls started [enjoying]; they thought he was doing that on purpose. When he came off stage he said, “What did I do? What’s going on?” Me and Bill started laughing. “Well,” we said, “when you started shaking your legs they started screaming.” He said, “I wasn’t doing anything on purpose,” which was true, but he was a fast learner.'

“Good Rockin’ Tonight” deserves a central place in the canon because - more so than “That’s All Right”- this rockabilly classic introduced Elvis Presley to the world. Scotty Moore had fun recalling an innocent moment from the summer of 1954 when Elvis played two shows in a day at Memphis’s four-thousand-capacity version of the Hollywood Bowl, the Overton Park Shell. During the afternoon set, Presley only sung ballads and did not fully win the crowd over. In the evening, he played his local hit and more up-tempo numbers, shaking his leg in time to the music. Two years later, the singer recalled, “I was scared stiff. And it was my first big appearance in front of an audience.”

At that point, Elvis’s leg shaking was a way to disarm anxiety arising from his emergent position as a star. Although he grew confident as a tease in his stage role, his slight nervousness worked as an element that positively informed his sexual chemistry. When he returned to the Overton Park Shell in 1955 for Bob Neal’s eighth annual Country

Music Jamboree, however, the song he used to prompt a wild audience response was “Good Rockin’ Tonight.” Country singer Webb Pierce, who was on the same bill, knew he had been trumped. All he could say was “Sonofabitch!” The number showed that Elvis could be sexy and dangerous, edgy and fun, all at once. As Peter Carlin said, Elvis “not only looked like a sexed-up riot, but sounded like one too.”

Years before Elvis’s Sun release, Roy Brown, an ex-boxer from New Orleans, established himself as a successful R&B artist. His music took a special form: jump blues infused by gospel swing. Brown recalled:

Cecil Gant was at the Dew Drop Inn and Wynonie Harris was appearing at Foster’s Rainbow Room. . . He was flamboyant, he was a good looking guy, very brash. He was good and he knew it. He just took charge, I liked the style. Anyway, when I was in New Orleans I had one suit and there was no bottom in my shoes, I had cardboard. I didn’t even have a bus fare to the club. So I wrote “Good Rockin’ Tonight” on a piece of brown paper bag, something you might buy at the grocery store, you put onions in, and I wrote out “Good Rockin’ Tonight” on this brown paper sack and I took it to Wynonie Harris.

Wynonie Harris was, despite his rather country-sounding name, a magnificently slick R&B singer. When he saw Brown coming, he asked the amateur to stop bothering him before he had even heard the composition. Brown got over the rejection and started performing his own song to scout label attention. On the strength of it, he was picked up by De Luxe Records. When the single took off in 1947, Harris took note and decided that he would cover “Good Rockin’ Tonight.” The next year his jazzy and very swinging version became a much bigger R&B hit than Brown’s release.

One of Brown’s first follow-up releases was called “Mighty, Mighty Man.” De Luxe put it out in 1948 as a shellac pressing. The label lost its legal foundation after Syd Nathan gained a controlling stake. Brown was eventually transferred to Nathan’s talent roster at King Records. In January 1953, a King Records single called “Hurry Hurry Baby” was credited to “Roy Brown and his Mighty-Mighty Men.” In mid-September of the following year, when the Blue Moon Boys recorded “Good Rockin’ Tonight” down on Union Avenue, Elvis included the “Mighty Man” phrase. Sam Phillips chose “Good Rockin’ Tonight” as an R&B-style A-side for the group’s second single which was released on 25 September.

Talking about his faster music, Elvis said to one journalist in 1956:

The colored folks been singing it and playing it just like I’m doing now, man, for more years than I know. They played it like that in their shanties and in their juke joints and nobody paid it no mind ’til I goosed it up. I got it from them.

This chimed with Brown’s own view. After he found out that his song had been covered by a white boy, Brown later recalled: “Elvis was singing this song with a hillbilly band but he never did sell because he hadn’t become Elvis as yet, you know.” For Blues Unlimited magazine, in 1977, Brown expanded his thesis:

What really happened, when these guys got on television, and do all these dances they had copied us from guys like the Drifters, the Little Richards but we had never gotten the chance to perform before the white kids and they thought all these guys, the Elvis Presleys, were original with that stuff. They weren’t original. We’d been doing that stuff for years.

Regarding segregation and prejudice in the media, Brown had it about right. He also had a rough time fighting for his rights and royalties in the early 1950s. However, there was a key difference between the R&B versions of “Good Rockin’ Tonight” and Elvis’s take. As Billboard explained in its Spotlight review, Elvis’s style was “both country and R&B,” and it could “appeal to pop.”

What Sun 210 delivered, then, was a young country singer who was much more confidently rocking - cheekier and perhaps more carnally knowing - than he had ever been on his first single. Elvis was charting the form of rockabilly, defining exactly what it could mean. New dimensions could be heard in his impassioned live version of Brown’s song captured when the Blue Moon Boys played at the Eagles’ Hall in Houston on 19 March 1955. The Hillbilly Cat got so swept away by his performance that he added an extra “We’re gonna rock!” right at the end, as if to drive the song home. A sexy, truck-driving space alien had just hit America, and its name was Elvis Presley.

(EIN NOTE: Each article includes multiple references - not included here - which are followed up in the last section of the book)

|

“Working on the Building” ('His Hand in Mine' LP 1960) #73

Early in March 1960, Elvis left Germany, Priscilla, and what Life magazine called “hordes of palpitating Fräuleins” when his army tour of duty came to its end. Two weeks before Norman Taurog’s romcom GI Blues hit cinemas across America, the fans received another treat, when, in November, RCA released Elvis’s first gospel album, His Hand in Mine. Side two was rounded out with a short but spirited rendition of Winifred Hoyle and Lillian Bowles’s “Working on the Building.” Its biblical origins lay in the New Testament verse: “According to the grace of God which is given unto me, as a wise master builder, I have laid the foundation, and another buildeth thereon.” Quite how such inspiration was adapted for the gospel lexicon is open to question. “Working on the Building” is based on the long-running practice of singing in the round. It has a wonderful, lilting feel. One version became a regular hymn in Holiness (Pentecostal) churches.

BB King said he borrowed the song from church and added it to his repertoire when he worked the streets in 1959. On the Crown LP BB King Sings Spirituals, he delivered a storming blues gospel interpretation, complete with a hand-clap intro and funky organ backing. Elvis’s Nashville recording was something else. Observing the singer’s ambition to join a gospel quartet, Ernst Jørgensen noted, “As the song progressed Elvis seemed to relish stepping from the solo spot to become part of the group performance, as he had so desperately wanted to do back in 1953.” Instrumental backing on the Presley version still sounds distinctly farmyard, like some sprightly country ditty. When Elvis comes in, he puts the track right back on course; arriving quietly, confidently, and smoothly—like some wonderfully smoky jazz man—saturating the number with his silky, understated vocals. As a spirited backing singer, he gives the song lift, then rises to the occasion, adding to the growing chorus of voices and instruments.

Gordon Stoker claimed that he reminded Elvis of “Working on the Building” at the sessions for His Hand in Mine. Stoker joined the Jordanaires in 1949, the same year as the group secured its place on the Grand Ole Opry. Capitol’s standard 10-inch shellac pressing of “Working on the Building” became a hit the following year. Though a little slower than Presley’s later take, this 1950 version was swinging, swinging, rousing, and alive with the group’s love of harmony.

Not long after, Brother Joe May, the dynamic African American “Thunderbolt of the Midwest” who was born just over forty miles east of Memphis in a little town called Macon, Tennessee, recorded a new version with the Sallie Martin Singers. May’s fabulous a cappella R&B performance of “Working on the Building” came out on Art Rupe’s Los Angeles label, Specialty Records. During his gospel renditions, the “Thunderbolt” brimmed with what Cornel West calls black prophetic fire. His magnificent, compelling vocals were on par with the gospel sermons of Aretha Franklin’s father, the Reverend C. L. Franklin. Indeed, “Thunderbolt” approached the screaming intensity of Archie Brownlee, the highly charismatic leader of the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi. Elvis may well have known about Brother Joe May’s version because the beginnings of both their takes shared a certain understatement. There were, however, much earlier interpretations of “Working on the Building” and those likely played a bigger role in his 1960 arrangement. To decipher the mystery of the Presley rendition, it is necessary to travel back before the 1950s.

Discussing “Working on the Building,” the encyclopedia writer Adam Victor speculated, “Elvis likely first heard this song at his mother’s knee- her favourite group the Blackwood Brothers recorded it when Elvis was just two.” The claim, however, is hard to substantiate.

It seems more solid that Elvis had more than one Blackwood Brothers’ RCA Victor record in his collection, including their 1954 single “His Hand in Mine.” The Tuskegee Quartet has been mooted as recording an early rendition of “Working on the Building.” Firm evidence shows that in 1934 the Carter Family released a similar version of the song in typical, old-time country style. It repeated the title and chorus lyrics but was called “I’m Working on a Building.” The song was a prototype and unique too in many ways. In the summer of 1936, the Heavenly Gospel Singers pursued what was perhaps the first, clear spiritual take of “Working on the Building” for release on Bluebird Records. Several black gospel groups then claimed Hoyle and Bowles’s song in the 1940s. It was recorded by the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi for Coleman Records, the Swan Silvertones for King, the Soul Stirrers on Aladdin, and the Soul Comforters for De Luxe.

These versions evidently inspired Elvis’s delivery. He drew together the snappy style of black gospel singing with a fresh, country backing. Though Stoker reminded Elvis Presley of “Working on the Building” in 1960, it appears likely that the singer was already keen.

Polk Salad - Japanese Single style!

“Polk Salad Annie” ('On Stage' LP 1970) #8

One of the interesting things about Elvis’s career was the way that sometimes he came around to doing the opposite of what he had done before. His rock ’n’ roll was often contrasted to the sedateness of Patti Page’s 1950 hit “Tennessee Waltz,” but in 1966 Elvis did his own home taping of the song. Equally, he had been ribbed on The Milton Berle Show - where the host played his hick twin brother, Melvin (“Television—what the heck is that?”)—and later he participated in mediocre Southsploitation features like Follow That Dream and Kissin’ Cousins. In 1970, however, Elvis presented his own update of the genre by covering Tony Joe White’s “Polk Salad Annie.” Of course, America had changed out of all recognition by then. It was no longer quite so acceptable to dismiss the South as backward. For younger people, the place was cool. By curating a quirky tale of Southern life, Elvis was able to delight his Vegas audiences with one of the ultimate cabaret tunes of the era. What was unusual about it was that he stuck quite close to the original version, rather than, as was customary practice, opting to reshape it.

Southerners used to pick poke weed and make “polk sallet” from its asparagus-like shoots. “Polk Salad Annie” was therefore based on a fictionalized reality. Poke weed had to be gathered by hand. It was one of the earliest of the annual crop of spring greens. From the middle of the twentieth century right through to its end, the Allen Canning Company of Siloam Springs in Arkansas paid pickers to gather a mess of it ready for preservation in tins. The main market for canned polk sallet consisted of those who fled the South during the Dust Bowl era and settled in other parts of the country. It is easy to see why Tony Joe White’s number became a crowd-pleasing staple of Elvis’s 1970s set. The song kept everything light and funny. It offered an unsurpassed blending of funk and gospel within a highly contemporary rock format. Hardly surprising, then, that funk soul brother Clarence Reid covered it in 1969. Tom Jones released his own take in 1970. The writer of “Polk Salad Annie” also performed a duet on television with Johnny Cash. None of those quite touched Elvis’s effort for sheer Vegas glamour.

During his intro to “Polk Salad Annie” from the rehearsal section of That’s the Way It Is, Elvis launches into a series of comedy yaps but then returns to finish a sharp cut. Director Denis Sanders emphasizes the song’s dynamism with split-screen (though he also pairs the soundtrack with irrelevant shots of hotel catering activities). After rushing through “All Shook Up” during the final show, Elvis unleashes the song, evidently aware of its devastating potential. In rising moments of electric anticipation, he playfully assumes the role of an army sergeant, counting out a comedy “hup two three four.” As the number reaches its climax, Sanders’s camera - after showing shots of the audience transfixed- rapidly pans in and out on Elvis, emphasizing his dynamic stage moves. The singer finally jumps up and cuts the song to its close. He is rewarded by thunderous applause.

“Polk Salad Annie” allowed Elvis to display a masterful control of his band. It’s not surprising that the live incarnation usually featured a funky extended bass solo from Jerry Scheff. The Californian bassist began his working life with interests in jazz and classical music. He became a favored session player whose career scaled new heights when he produced a studio hit in 1966 for the Association. He joined Elvis’s Vegas band when it formed in 1969, taking a break from February 1973 to April 1975. Even while working with Elvis, Scheff did other things, including bass parts for the Doors’ 1971 album, LA Woman. He and percussionist Ronnie Tutt also toured with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends. The Bramletts’ band was a unique Southern blues rock ensemble. It functioned as a training ground for many notable musicians. Even though the Vegas shows only contained twelve to fifteen songs, Elvis probably rehearsed more than one hundred with the band. He wanted to make sure they were flexible enough to cope with anything that would be thrown at them. Scheff was challenged by the demand for spontaneity. He recalled:

The music was so intense. It was a kind of punk lounge music. I was playing very busy parts and to this day, I can’t listen to any of the albums we did, because everything is so intense feeling. . . . I went right on stage with no rehearsals. During that first part, ’69 to ’73, we would play and it was just WHAAMM!!!

When Scheff rejoined Elvis in 1975, the music was slightly mellower, and he was better prepared for it. Nevertheless, his description reveals the way that the band was kept on its toes. Playing had to be a reflex response. Elvis was attuned the audience, and the band was attuned to Elvis. Energetically, “Polk Salad Annie” was “punk lounge music”: a sister tune, in many ways, to “Suspicious Minds.” Both offered exciting vamps and both culminated in an immense release of energy, signified by squealing horns, as Elvis cut to his musical climax.

Ultimately, “Polk Salad Annie” was therefore a song that showcased how knowing and feral Elvis could be. For that reason, it is almost impossible to tire of hearing his take on Tony Joe White’s number. Right from those anticipatory hand claps, it welcomes listeners, building excitement and inviting them “down South” in a way that is sexy and commanding at the same time.

Punk lounge music, indeed.

From EIN's lengthy review - Verdict: Counting Down Elvis His 100 Finest Songs is one of finest Elvis book releases released this century. Exceptionally well researched and thoughtfully considered, it is stimulating, thought provoking and a joy to read (and sometimes disagree with). Counting Down Elvis should be in every fan’s Elvis book library.