THE MEMPHIS SESSIONS

It seems impossible that it was fifty years ago this month that Elvis walked into American Studios in Memphis and started work on what are probably his most celebrated sessions, maybe even better than those made at Sun. Not as influential, of course, but certainly deeper and darker from both the point of view of lyrics and Elvis’s emotional involvement. He was no longer a (relatively) innocent teenager singing about love to his sweetheart, but someone who had really experienced love as an adult. He could also sing about loss in a way he couldn’t fifteen years earlier, for he had experienced that, too. In other words, he had lived, and he seemed to pour all of his experiences into the recordings at America, and didn’t care about laying bare his soul. In fact, he knew he had to. This was make or break.

|

Let’s take a look at some of the most notable songs recorded.

A few months earlier, one could have been forgiven for thinking that the bell sounding at the beginning of Long Black Limousine (the first song recorded) was the death knell for Elvis’s career, but the TV special that aired in December 1968 managed to prevent that. Elvis bases his version of Long Black Limousine on the recording by O. J. Smith, and, as good as Smith’s recording is, Elvis’s is a tour-de-force. Long Black Limousine tells the story of a girl from a small town who left the narrator behind to go and live in the city, boasting that she would return rich and in a “fancy car,” only to fulfil her prophecy at her own funeral, with the fancy car being a hearse. Elvis knows this story, he knows the frustrations the girl felt, and he also knows that he could one day be in her place.

Elvis yells out the opening lines of Wearin’ that Loved on Look, an effective mix of soul, funk and rock ‘n’ roll that would become the first track on From Elvis in Memphis, the first album released from the sessions. This was a track that was perfect for Elvis, and he’s clearly having a ball, even adding his own “shoops” during the chorus almost as if he is singing to (and with) himself.

|

You’ll Think of Me is different and unusual. It’s a long song where are no real choruses, just verse after verse with a nice twist in the lyrics at the end, and shows Elvis being interested in more challenging material. He appears to be relishing the chance to get inside a character and tell a story – a real story this time, not a piece of bland fluff for a Hollywood film. Mort Shuman wrote the number, and later told Trevor Cajiao, “I love that song. I didn’t particularly like the way the arrangement was done on it… I think they could’ve done a better job on You’ll Think of Me. That was when I was sorta into my period of being influenced by Dylan and the whole San Francisco type thing, so it was a very folky kind of thing.”

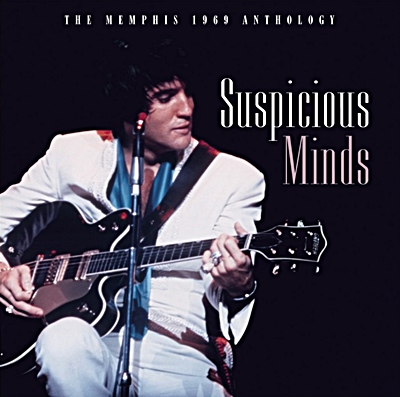

I’m Movin’ On is an old country warhorse that Elvis gives a makeover, but he did at least have a version to base his own on here. The Box Tops had included a great rendition of the number on their third album, Non-Stop, and this was the version that Elvis modelled his on. What’s added in the Presley recording are his soul-filled vocals and the brilliantly-judged backing vocals during the choruses that tend to give the song something of a gospel feel. Perhaps the best version was the alternate performance included on the Suspicious Minds double CD release.

|

Gentle On My Mind was a much newer song, that had already become a country standard. The recordings by John Hartford and Glen Campbell had been pure unadulterated country, but Elvis’s version has, in many ways, a much heavier sound that mixes country with elements of soul and even gospel, and all of it underpinned by a driving bass line. What is most noticeable here compared to other recordings is just how masculine Elvis’s performance is. As with Dean Martin’s version of the same song, we can actually imagine Elvis with his “beard a roughenin’ coal pile” – an image that isn’t encouraged by Glen Campbell’s rendition.

Don’t Cry Daddy kept things in a largely country vein, and the song would provide Elvis with one of four hits from the two sets of sessions in Memphis. Views on the song vary depending on how much the listener can stomach the rather saccharine nature of the lyrics. Variety called the song a “potent tearjerking ballad handled in standout style.” Elvis sings the song beautifully and with sincerity, but it hasn’t grown old particularly gracefully and is just too maudlin and sentimental for its own good.

My Little Friend is hardly a great song musically, but the lyrics about a man remembering his first love are interesting and often manage to capture the innocence and excitement of adolescence. It’s a surprisingly adult song in many ways, particularly in its memories of first sexual experiences, most notably in the lines: “I learned from her the whispered things / The big boys at the pool hall talked about.” We all know what the narrator is talking about and probably also remember those overheard conversations of older kids as we grew up too. Elvis tells the story simply, and we believe every word.

|

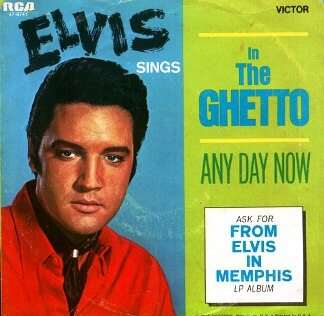

Between 1968 and 1970, Elvis recorded a number of songs with a social conscience theme – something he never did in other periods during his career. Following on from Clean Up Your Own Backyard and If I Can Dream, In the Ghetto didn’t, therefore, appear out of nowhere. Written by Mac Davis (who also wrote the maudlin Don’t Cry Daddy), the track was described in one newspaper as a “message song of the disadvantaged in a Chicago ghetto.” Elvis immerses himself totally in the story at the heart of the song. Peter Guralnick writes that “the singing is of such unassuming, almost translucent eloquence, it is so quietly confident in its simplicity, so well supported by the kind of elegant, no-frills small-group backing that was the hallmark of the American style – it makes a statement almost impossible to deny.” Guralnick’s words are particularly apt when one listens to the awful attempt to update the song on the recent album with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Robbed of that simplicity and the “no-frills small-group backing,” the song is not anywhere near as moving or affecting as the original, perfectly-judged, studio master.

I’ll Hold You in My Heart is incredible. Elvis takes this old country song and sings it over and over in the same manner as take 2 of You’ll Never Walk Alone and Saved during the TV special from the year before. Elvis wrings every last drop of emotion out of it and yet, surprisingly, none of its lengthy running time seems forced or contrived. Peter Guralnick raved in Rolling Stone, writing that “nothing could better exemplify the absorbing character of Elvis’ unique and moving style. At the same time nothing could more effectively defy description, for there is nothing to the song except a haunting, painful emotionalism.”

|

The first set of sessions ended with the classic Suspicious Minds, a track that Billboard referred to as an “outstanding performance.” For a recording so artistically brilliant it was also remarkably commercial. The sudden drop to half speed during the bridge makes the listener take notice even on the first hearing and, while the fade-out-fade-in ending could (and perhaps should) be viewed as a gimmick (and one that producer Chips Moman is said to have hated), it also meant that the song was instantly memorable and recognisable.

Elvis returned to the studios the following month, and continued where he left off.

Stranger in My Own Home Town had been written and recorded by Percy Mayfield in 1963, but here Elvis doesn’t just alter the feel of the song but gives it a complete transformation. The length of Elvis’s version is nearly double that of the original, with Elvis singing the same two verses over and over again, subtly changing the melody each time. Unusually, there is an instrumental introduction lasting a full verse, and then a number of instrumental breaks over which Elvis improvises partly off-mic and tells the band to “give it clout.” Everyone seems to be having a great time and, more than almost any other Elvis recording, this portrays the great joy that music-making can bring. What is more, this is another example, rather like 1960’s Reconsider Baby, of Elvis showing just what a great blues singer he was, and he would return to the song in a more traditional slow blues tempo during rehearsals for his summer 1970 Las Vegas season.

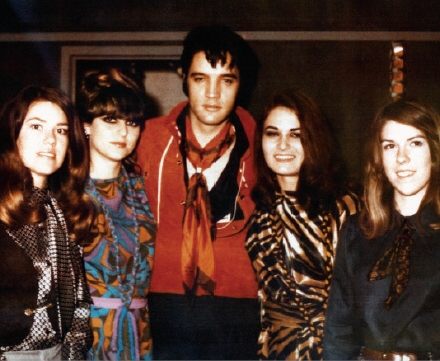

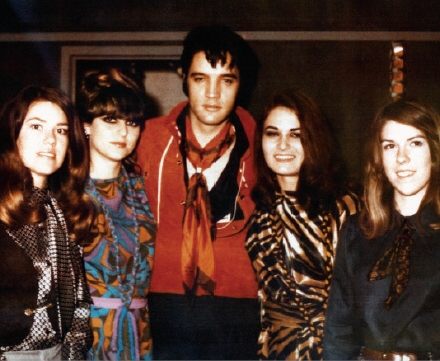

Elvis with producer Chips Moman

Power of My Love is an edgy rock number in waltz time that sees Elvis digging deep and giving a dramatic, almost threatening, performance. It seems almost bizarre that this great number, one of the highlights of the session, was written by Giant, Baum and Kaye – one of the most prolific (and bland) of all the songwriters of the Hollywood years. While they had shown their capabilities in the past with Devil in Disguise and City By Night from Double Trouble, they were also responsible for such dross as Queenie Wahine’s Papaya, Beach Shack, and Wisdom of the Ages.

Do You Know Who I Am sees Elvis firmly back in quiet, understated ballad territory in a song that lyrically seems like a kind of sequel to Just Tell Her Jim Said Hello. In that song, the narrator has just spotted an ex-girlfriend across a crowded bar or restaurant. In Do You Know Who I Am he takes the opportunity to go over and say hello. Once again, Elvis gets to develop his story-telling skills, and gives a far more convincing acting performance here than in many of his movies.

|

The same can be said for Kentucky Rain, a rather more dramatic song with a strong narrative. Here, the singer is looking for the lover that left him without saying goodbye the week before. This was the last of the Memphis session songs to be released as a single, and the only one not to reach the top ten in America, stalling at #16, and only reaching #21 in the UK. It is hard to figure out quite why the track did less well than its predecessors for it’s a strong song and Elvis’s performance is totally compelling. Indeed, James E. Perone wrote that Kentucky Rain is “among the strongest 1960s’ performances that Elvis gave” and that it has enough “genre-blurring vitality [that it] transcends many other releases from the 1960s.”

Only the Strong Survive sees Elvis back in soul territory, covering Jerry Butler’s U.S. hit single. Elvis puts in another strong performance here, but his version follows the original very closely, which is rather a shame when compared to the songs from these sessions where Elvis took a song and transformed it into something purely his. Even though it took nearly thirty takes to get it right, the arrangement barely moved away from Butler’s own at all, although that is not to take away from the quality of Elvis’s vocal.

Any Day Now, written by Bob Hilliard and Burt Bacharach, has an awkward, hard-to-sing melody (did Elvis ever sing a more difficult song?), but Elvis seems to manoeuvre around it with ease. The bridge gives the appearance of dropping in tempo, but it’s just an illusion created by the sparser instrumentation. Elvis’s performance manages to retain some of the soul aspects of the number that were present in Chuck Willis’s original, but also seems to merge them with a vocal that clearly draws on the influence of Tom Jones, who had released his own version on his Green Green Grass of Home LP in 1967. Despite the difficult, angular melody, Elvis went as far as rehearsing the song for his live shows a couple of years later, although it never made it to the stage.

Beyond the songs highlighted above, more than a dozen others were recorded. These included quality album tracks such as After Loving You through to the abysmal mess of Hey Jude. But, Hey Jude aside, even when he was coasting during these sessions, he still seemed to be on fire. Check out how he takes Bobby Darin’s I’ll Be There and steals it from right under the composer’s nose, giving it a wonderfully warm and flowing performance that seemed to evade Darin.

|

The material from the Memphis sessions was spread over two albums, a number of single sides (including four hits) and budget albums, with Hey Jude escaping quietly three years later on the Elvis Now LP (and the less said about that the better).

From Elvis in Memphis may be Elvis’s greatest album, but the notion that it was an instant classic is really not true. That isn’t to say that there wasn’t some very good reviews. Billboard stated that “Elvis returns to Memphis, where he began his sensational career, and the return is really an event. He’s never sounded better, and the choice of material is perfect.” Meanwhile, Variety referred to the release as a “tightly socked disk with adept Memphis backup.” Elsewhere, readers were told that “admirers of Elvis will surely want From Elvis in Memphis and others will enjoy an excellent first taste of Presley in this album.”

Other reviews were decidedly mixed. Mark Wolf, for example, praised the second side of the album, but complained about the “inexcusably poor balance of the recording.” However, he also described the first side as “merely good” with the exception of I’ll Hold You in My Heart which is seen to be “lousy” and “four and a half minutes of Elvis imitating Elvis.” Mary Campbell in the Bridgeport Post referred to the LP as “quality country” and “very listenable.”

In the Los Angeles Times, Pete Johnson said that the record:

…owes little inspiration either to Sun Records or to Stax. The rhythm section used on the album rarely gets off the ground, horns are scarce and generally insipid, the musical arrangements are Hollywoodish and the simply-structured performances seem to spring more from laziness than deliberation on the part of the producer and arranger. What saves the album, though, is Elvis’s voice.

Perhaps most derisive was Albert Holbert in the Star Tribune who wrote that “some of Elvis’s country stuff is sickening and most of his religious stuff will make you throw up.

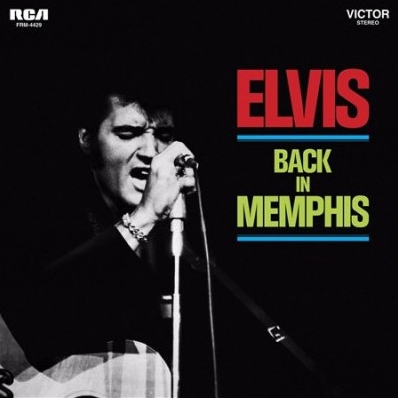

The second album, now generally referred to as Back in Memphis, was originally issued as part of a double album also containing an LP of live performances from August 1969. From Memphis to Vegas/From Vegas to Memphis generally received better reviews that the previous album, but only because of the live disc. Critics’ opinions were much more divided over the Memphis material that was included.

The New York Times stated that the “Presley style dominates whatever he touches, and even the new pieces become quickly and comfortably familiar.” A week later, the same newspaper printed a second review, this time by Albert Goldman, who admits that “this is Elvis Presley’s year,” but fails to discuss the studio recordings at all. Robert Hilburn wrote that the studio recordings were “a disappointment. Not only is his delivery more restrained, but most of the material is extremely weak. Only on Do You Know Who I Am, From a Jack to a King, and Without You (sic) does he generate any impact at all.” In the Philadelphia Inquirer, Jack Lloyd wrote that “the new session…lacks the impact of the Vegas sides, but still contains some pleasant music.” Variety goes as far as saying the “studio record features the best of Memphis backing for newer material in the pop vein,” but doesn’t include a single song from that disc in its list of “standout” tracks.

It seems somewhat remarkable now to think that the thirty or so recordings made by Elvis during the first two months of 1969 were not critically acclaimed at the time, especially given their status today as some of the best work Elvis did. The problem was not that the critics had a problem with Elvis, for the live recordings from later in the year were extremely well-received. But those live performances were mostly about Elvis reliving former glories by revisiting his old hits. As with the TV special, it was the revival of those hits that garnered the most positive reviews. In other words, despite the wonders of the Memphis sessions, some people still lived in the past, believing that nothing Elvis could do (even when it was this good) would match the wonders of his first recordings.

|

For example, despite giving From Elvis in Memphis a glowing review, Peter Guralnick still wrote:

And yet it’s still not the same. …You can’t recapture the innocent ease of those first sides, you can’t bring back the easy innocence of new adulthood, whether for listener or singer. What is so striking about the sides cut for Sun Records, even today, fifteen years after their release, is the freshness of style, the cleanness and the enthusiasm.

The problem here is that Guralnick’s yearning for Elvis’s early style seemingly has little to do with Elvis himself. In fact, he had just spent two pages of a magazine praising his most recent work. No matter how much it might be denied, the comments he makes about the Sun sides here have little to do with their quality and much more to do with Guralnick’s yearning to recapture the wonders of his own adolescence. By 1969, Guralnick was a grown man, and not a twelve or thirteen-year-old boy who was, no doubt, captivated by Elvis’s early records. By his own admission here, no matter how good Elvis was in 1969 (or after), it would simply never be good enough – and it’s clear from the other reviews of this material that Guralnick was not alone.

Much has been written about Elvis’s work in the final seven or eight years of his life, and much has been said about the material he chose to record, the genre he chose to record in, and the arrangements he chose to employ. Blame has been put on all those things when critiquing Elvis’s final decade but they are often just a scapegoat. Even if the quality of those final years was as high as these masterful recordings in Memphis, they still wouldn’t have been good enough for those critics who were not able to face the idea that they had to grow up, and that their idols had to grow up too and sing about more serious things than playing house, teddy bears, or asking someone to wear a ring around their neck.

Unfortunately, Sony haven’t released a commemorative set at retail level to mark the anniversary, unless they decide to do so later in the year.* A 3CD set in the same format as the reissue of A Boy from Tupelo would have been very nice indeed, including all of the masters and some carefully chosen outtakes. It seems odd that the 1973 Stax recordings have got this treatment, but not the 1969 material. Perhaps it will come later in the year in time for the 2019 Christmas market, although that would run the risk of it being overdubbed with new arrangements played by an Alaskan university jazz band (“as Elvis would have wanted”) and duets featuring Justin Bieber and Barry Gibb on Power of My Love and Stranger in My Own Home Town respectively.

* EIN feels certain that a Deluxe Box-Set of "ELVIS: The Memphis Sessions" will be release this year and included as part of the Elvis Week 2019 celebrations

Spotlight by Shane Brown.

-Copyright EIN January 13, 2019

EIN Website content © Copyright the Elvis Information Network.

Click here to comment on this article

Shane Brown is the author of Reconsider Baby: Elvis Presley, A Listener’s Guide, and has recently published the extended and revised 2nd edition of Bobby Darin: Directions. A Listener’s Guide.

|

|

Book Review "Reconsider Baby: Elvis: A Listener's Guide": Elvis Presley made over 700 recordings during his life. This book by author Shane Brown examines all of them. Session by session, song by song, Reconsider Baby takes the reader on a journey from Elvis’s first recordings in 1953 through to his last performances in 1977.

This significantly expanded and revised edition of 2014’s Elvis Presley: A Listener’s Guide provides a commentary on Elvis’s vast and varied body of work, while also examining in detail how Elvis and his recordings and performances were discussed in newspapers, magazines, and trade publications from the 1950s through to the 1970s.

The text draws on over 500 contemporary articles and reviews, telling for the first time the story of how Elvis and his career played out in the printed media, and often forcing us to question our understanding of how Elvis’s work was received at the time of release.

Can another detailed examination into Elvis' musical legacy really be worth buying? (Hint, the answer is a big YES!)

Go here as EIN's Piers Beagley reviews the newly expanded look into Elvis' musical legacy, including some choice book extracts...

(Book Reviews, Source,ElvisInformationNetwork)

|

|

More great articles by Elvis author Shane Brown |

'The Steve Allen Show' EIN Spotlight: Much has been written about The Steve Allen Show appearance over the years and with each retelling of the story, much of the information required to give a fair hearing to Allen is conspicuous by its absence. Recent articles in ETMHM as well as Elvis Files magazine still repeat the usual story.

But was Steve Allen really the rock'n'roll hating villain as usually portrayed in the Elvis story?

In the past, this might have been done because some of the information was not available, but with the appearance of online newspaper and magazine archives over the last decade it is much easier to piece together the complete story rather than the fragments of it that have been passed down amongst Elvis fans over the last sixty years.

After all, alongside Parker, Allen has become the second of the pantomime villains in the Elvis story, and it is time to investigate anew in order to see what really happened, and what Allen’s real relationship with rock ‘n’ roll was.

In this fascinating new article, EIN contributor Shane Brown investigates the truth behind ELVIS on the Steve Allen show...

(Spotlight, Source;ShaneBrown/ElvisInfoNet)

|

|

'Orgies and Orgasms: Presley in the Press 1956'- an in-depth Spotlight: By the beginning of 1956, everything was in place for Elvis Presley to burst onto the national and international music scene. Within weeks of his signing to major label RCA he would record Heartbreak Hotel, his first single for RCA and his first to reach number 1 in the U.S. charts, and then, at the end of January 1956, he would appear on national television for the first time.

Despite all of the success that 1956 would bring Elvis, with three singles and two albums reaching the top spot in the U.S. charts, the year would also prove to be a difficult one when it came to his treatment in the national and international press.

Mainstream media published reviews such as...

"Every girl watching him sees herself as Elvis’ partner in his fantastic writhing orgy"

and "Presley is suggesting he is about to have a self-induced orgasm!"

So, let’s go back in time and examine how a single television performance in June 1956 resulted in a change of attitudes towards Elvis within the media from little more than curiosity about the new phenomenon to downright hostility and revulsion.

Go here as EIN contributor Shane Brown investigates the phenomenon of Elvis in 1956 - and what the media made of this new, and middle-America shocking, entertainer.

(Spotlight, Source;ShaneBrown/ElvisInformationNetwork) |

|

"Reconsider Baby: Elvis: A Listener's Guide" 2017- Shane Brown Interview : Since Elvis's Since Elvis' death in 1977, thousands of books have been written about Presley, but very few concentrate on the most important thing: the music.

Shane Brown's 2014 'Elvis Presley: A Listener's Guide' was a first in its very detailed look into the remarkable and yet often frustrating musical legacy that Elvis left behind.

Now in 2017 Shane Brown has revisited his original Elvis guide expanding it to include even more detailed insights - as well as including a large number of recently unearthed contemporary reviews from the time.

EIN was fascinated by the idea of an even bigger examination of Elvis' musical legacy and Shane Brown kindly agreed to be tell us all about his new expanded look at Elvis' music -

Questions we ask include..

- What expanded insights does this new edition provide?

- Why do a second edition?

- How many contemporary reviews from the time have you unearthed?

- Do you think that the Media understood Elvis' musical ambitions?

|

|