|

|

‘Every girl watching him sees herself as Elvis’ partner in his fantastic writhing orgy’: Elvis Presley and the Press in his Breakthrough Year. Despite all of the success that 1956 would bring Elvis, with three singles and two albums reaching the top spot in the U.S. charts (and that’s without mentioning the release of Elvis’s first film), the year would also prove to be a difficult one when it came to his treatment in the national and international press. So, let’s go back in time and examine how a single television performance in June 1956 resulted in a change of attitudes towards Elvis within the media from little more than curiosity about the new phenomenon to downright hostility and revulsion.

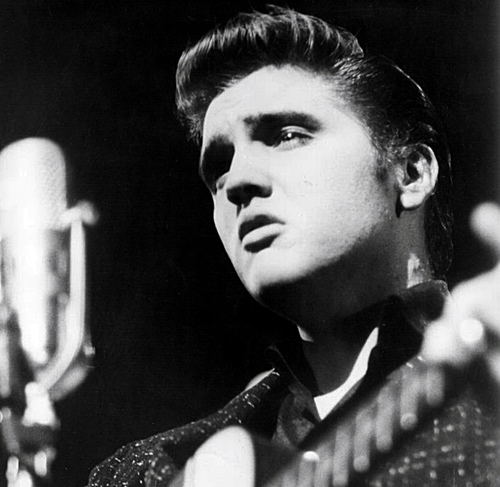

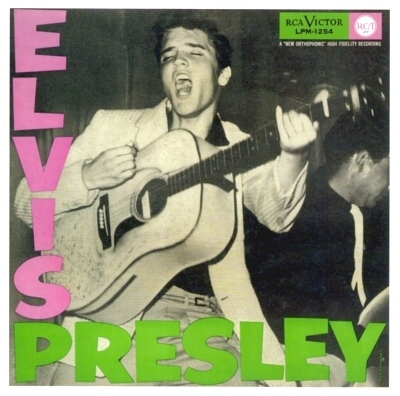

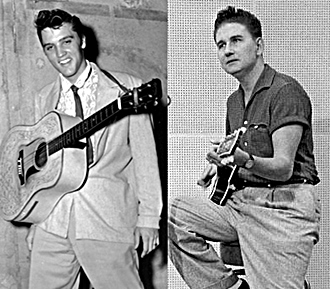

Elvis on his first national TV appearance, January 28th 1956, Stage Show

Elvis Presley’s first national TV appearance was on the January 28th 1956 edition of Stage Show (CBS, 1954-1956), hosted by big band leaders Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey. Rather strangely, Elvis didn’t perform Heartbreak Hotel, his first RCA single, until his third appearance on the series. By this point, he appeared to be causing little controversy beyond a few raised eyebrows. The trade journal Motion Picture Daily referred to him in advance of his fourth appearance as ‘an abandoned performer who plays and sings in a manner that Marlon Brando should, and doesn’t’ – no doubt a dig at Brando’s vocalising in the previous year’s film Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955). What is interesting (and largely forgotten) is that viewing figures for Stage Show did not significantly increase during Elvis’s six appearances.

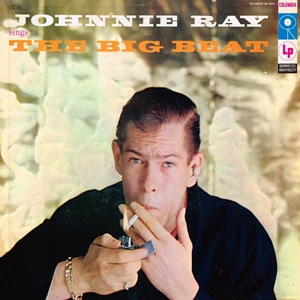

A number of publications of the time saw Elvis as the obvious successor to Johnnie Ray. Presley’s parallels with Ray came early on. For example, in their review of Elvis’s first album, Variety stated that ‘Elvis Presley belts away in uninhibited style and his current click continues where the Johnnie Ray vogue of a couple of years ago left off.’ Later, Ed Sullivan was quoted as saying ‘I’d been told this guy was disrupting the morals of the kids, that his whole appeal was sensual. But all I saw was a pale carbon copy of Johnnie Ray.’ When the New York Times reviewed Elvis’s first album, they also compared Presley to the earlier singer, stating that Elvis was, ‘nominally a country singer, who has the most torrentially belting style since Johnny (sic) Ray’s early days.’ It’s also interesting that the newspaper, which would go on to criticise Elvis more than any other in the early years of his career, gives the album a surprisingly positive review. ‘On ballad numbers,’ John Wilson writes, ‘he takes off with a drive that is startling, hair-raising and thoroughly provocative.’

Elvis and the Dorsey Brothers

Not all writers were quite as positive, however. Gord Atkinson in the Ottawa Citizen, for example, was using the ‘C’-word about Elvis (‘C’ for ‘Controversial’ that is) as early as March 1956, but not in an entirely negative way. While bemoaning the fact that ‘it’s the gimmick today that seems to make recording stars,’ he does call Elvis ‘the most controversial and electrifying show business personality since Johnny (sic) Ray’ and notes that he ‘almost explodes before an audience.’ Over in the UK, relatively little was written about Elvis at all in the newspapers of the first half of 1956. Perhaps most notable was Lionel Crane’s article in the Daily Mirror, entitled Rock Age Idol. What is perhaps most notable here is that it introduces one of two themes that would recur in articles during the second half of 1956 and beyond: class. Elvis’s poor background and, in particular, his new-found riches, would be mentioned time and time again as the year went on. Here the writer quotes Elvis as saying ‘“Look at all these things I got … I got three Cadillacs. I got forty suits and twenty-seven pairs of shoes.” I asked him how he knew it was exactly twenty-seven pairs and he said: “When you ain’t had nothing, like me, you keep count when you get things.”’

Elvis first Milton Berle show - April 3, 1956 - aboard USS Hancock.

By the time of the second Milton Berle appearance on June 5, we start to get early signs in the press that Elvis was being viewed as a commodity as much as a serious artist. Vernon Scott’s article in the Schenectady Gazette on June 7 (but clearly written before the Berle appearance) is one of the first to find Elvis’s manager, ‘Colonel’ Tom Parker, blatantly and unashamedly selling merchandise – to journalists, no less. He gives Scott a postcard and says ‘this is for you…absolutely free of charge. Any fan who writes in gets one for nothing. Then, of course, if they want one of our souvenir packages can send in the attached order.’ Elsewhere in the same article, Elvis is asked why he sings ‘such off-beat songs. Elvis grinned, “I like rock and roll because it’s selling. But if I had my way I’d be singing ballads and love songs. Man, I’m no bopster or hipster. I’m from right back in the country.”’ While the vast majority of articles in the first five months of 1956 show curiosity, bemusement, and general head-scratching by the authors at the Presley phenomenon, that all changed after the performance of Hound Dog on the second Milton Berle Show appearance. The articles that appeared shortly afterwards condemning the performance set the tone for how Elvis was seemingly viewed by many adults and conservative America in particular for the rest of the year and beyond. It is easy now, some sixty years later, to wonder what all the fuss was about. However, television in America was viewed in contrasting and contradicting ways during the early-to-mid 1950s. On the one hand, it was seen as an instrument to bring the family together as one but, on the other, there was almost a sense of fear that it could also wreak havoc on the same family, not least because what children and teenagers liked to watch and what parents wanted them to watch were often vastly different to each other. Many saw the people they were watching on television as, essentially, being invited into their homes, and therefore they expected them to be on their best behaviour and act as they would expect their own family to act – and not everyone on television was obeying those unspoken rules. At the very centre of this issue was Milton Berle himself whose variety show was entitled in the early 1950s Texaco Star Theater. Lynn Spiegel writes that ‘Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theater (which was famous for its inclusion of “off-color” cabaret humor) became so popular with children that Berle adopted the persona of Uncle Miltie, pandering to parents by telling his juvenile audience to obey their elders and go straight to bed when the program ended.’

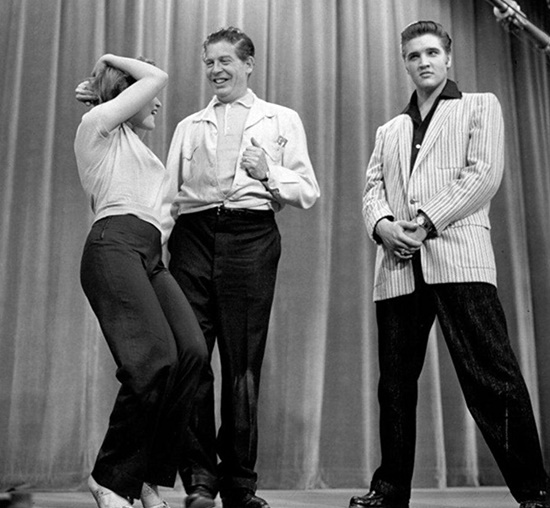

Elvis with Milton Berle and Debra Paget - June 5, 1956

Criticism of Berle’s television shows began in the early 1950s. Jack Gould (who would go on to be one of the most vocal critics of Elvis Presley in 1956) launched an attack on Berle’s show in the New York Times in September 1951. ‘Uncle Milty, the self-appointed guardian of the nation’s youth on Tuesday nights,’ Gould writes, ‘is a rather trying relative this season.’ He goes on to say that:

The Berle show had already been cancelled (and was only airing every three weeks during its final run), and so eyes appear to have been on the programme to see how Berle’s eight-year residency on a Tuesday evening would come to an end, and this, as much as Elvis’s appearance, accounts for the higher viewing figures. Elvis performed both I Want You, I Need You, I Love You and Hound Dog. The latter was a song that he heard performed by Freddie Bell and the Bellboys during Elvis’s largely unsuccessful stint in Las Vegas during late April and early May, and he quickly incorporated it into his act. The performance of the song on The Milton Berle Show was similar to that which he had been giving in concerts for the previous few weeks.

Elvis performs his infamous Hound Dog "Bump 'n' Grind" June 5, 1956

Dispensing with his guitar, television audiences got to the see the gyrations that Elvis’s live shows were becoming famous for. This would, perhaps, have been bad enough but, for the last minute or so of the song, he cut the tempo in half, upped the ante when it came to his suggestive movements, and treated viewers to what is perhaps best (and most often) described as a ‘bump ‘n’ grind’ routine. Guralnick states that he ‘goes into his patented half-time ending, gripping the mike, circling it sensuously, jackknifing his legs out as the audience half-screams, half-laughs, and he laughs, too – it is clearly all in good fun.’ As Berle was saying goodbye to his television show, with much of America watching, Elvis had inadvertently turned television into the unwanted monster and bad influence that much of middle America had been fearing. Watching Elvis’s performance now allows us to appreciate that the young performer was, as Guralnick suggests, just having a bit of fun – the end of Hound Dog is clearly tongue-in-cheek rather than intending to be viewed as something overtly sexual. But Berle’s history of ‘off-colour’ humour during his period as a TV show host only compounded the issue. The criticisms came thick and fast. One of the first and most scathing was Jack Gould in the New York Times who, as we have already seen, had been one of the most vocal critics of Milton Berle’s variety show. He wrote: ‘[Elvis’s] one speciality is an accented movement of the body that heretofore has been primarily identified with the repertoire of the blonde-bombshells of the burlesque runway.’ Elvis was essentially being compared to a female stripper but, as we have seen, these are not dissimilar accusations to those that Gould had already made against the Berle show when it was still Texaco Star Theater back in 1951, comparing Berle’s comedy routines to burlesque.

Col Parker, Elvis and Ed Sullivan, trying to cool the media outrage

Gould didn’t end his tirade on Elvis with the Berle show. With Berle no longer on air, he appears to have found in Elvis a new corrupting influence to campaign against. Picking up again three months later, following Elvis’s first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, Gould wrote that Elvis ‘injected movements of the tongue and indulged in wordless singing that were singularly distasteful.’ He ends his rant with the hope that Elvis ‘will do everyone a favour by pointing up the need for earlier sex education so that neither his successors nor TV can capitalize on the idea that his type of routine is somehow highly tempting yet forbidden fruit…If the profiteering hypocrite is above reproach and Presley isn’t, today’s youngsters might well ask what God do adults worship.’ While Gould might have been the most vocal opponent of Presley in the mainstream American media of the time, he certainly wasn’t the only writer at the time to compare Elvis to a female stripper - and attacks on Elvis’s masculinity were something which continued within newspapers and magazines right through until his death in 1977 and beyond. Pat Doncaster reminded UK readers in December 1956 that Elvis had been called ‘a male burlesque dancer’ and a ‘male Marilyn Monroe.’ Jane Newcomb, in the same month, repeats the stripper complaint telling us that ‘his wiggles have been variously described as: shagging, jazzing it up and acting like his pants were on fire. … They are all slang terms for the physical act of love. And this, most people agree, is what is selling Presley. Just plain, crude sex.’ Newcomb’s article continually refers to sex. ‘Every girl watching him sees herself as Elvis’ partner in his fantastic writhing orgy,’ she writes.

Elvis, Scotty Moore, Bill Black - the greatest band in heaven.

Another subject that often arose in articles about Presley at the time was that of his poor background, his upbringing, and his newfound wealth – with the rise from poverty to riches seemingly irking the journalists as much as Elvis’s gyrations. Many writers of the period seemed to think that somebody from Elvis’s poor background should stay there, and in not doing so, he was punching above his weight or trying to be something he was not. ‘He’s been criticised for his wild extravagance in buying four cadillacs,’ Jules Archer wrote. ‘But this seems an understandable spree for a youngster who is now being showered with sudden wealth, but who as a child only saw meat on the table once a month.’ Newspapers, particularly the New York Times, appeared to see this change in financial fortune as pretension. We can see this coming through most notably if we return to Jack Gould’s attacking piece from just after the Berle show aired. Gould writes that Presley was ‘attired in the familiar oversize jacket and open shirt which are almost the uniform of the contemporary youth who fancies himself as terribly sharp.’ Already we can see that the stance is being taken that the singer is a nobody attempting to be a somebody (‘fancies himself as terribly sharp’). In fact, Gould believes that Presley is only good at the ‘hootchy-kootchy,’ but then adds that is ‘hardly any reason why he should be billed as a vocalist’. It was almost inevitable that Elvis’s acting in his first movie would be criticised, particularly in the hostile New York Times. It was, after all, seen as Elvis trying to prove he was an actor when the newspaper wouldn’t even believe he could be called a singer. Again, it was being misinterpreted as something akin to pretension or, more simply, another case of Elvis trying to be something he wasn’t. Bosley Crowther’s put-down in his review of Love Me Tender is almost legendary: ‘The picture itself is a slight case of horse opera with the heaves, and Mr. Presley’s dramatic contribution is not a great deal more impressive than that of one of the slavering nags.’ It was only with the arrival of G. I. Blues in 1960 that Crowther would start to give Elvis some slack, and thereafter many Elvis films were given good reviews in the New York Times, particularly the light-hearted musical comedies. They weren’t, after all, attempts by Presley to be taken seriously as an actor as he was in the 1950s, but seen as an admittance that what he was good for was ninety minutes of fluffy nonsense with nice scenery, a few palatable songs, and pretty girls.

"Presley is suggesting he is about to have a self-induced orgasm!" - Films in Review

Perhaps the strangest (and certainly the most outrageous) comments on the film came in Films in Review, which is barely a review of the film at all and, instead, a tirade about Elvis and everything he stood for:

Elvis performs Hound Dog, October 28, 1956 - second Ed Sullivan Show.

But it was John S. Wilson who was the critic that perhaps made others think again about the musical worth of Presley. In his lengthy review of Elvis’s second album, he refers to Elvis’s ‘impressive, if sometimes distorted, talent.’ Elsewhere he praises Elvis’s mastery of the blues in So Glad You’re Mine, Anyplace is Paradise and Long Tall Sally, before stating that between his first and second album there has been ‘an improvement in his diction, in the use he makes of his strong natural voice, and in the thoughtfulness of his presentations.’ Despite the album being released in October 1956, the review was not published until mid-January 1957. By this point, Elvis had appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show on three occasions, with his final performance ending with Sullivan patting Elvis on the back and telling him he was ‘thoroughly alright.’ It was the start of the change of public (and critical) opinion towards Elvis. Sullivan, like Berle in the late 1940s and early 1950s, was treated by audiences as part of the family, invited into their homes each week, but Sullivan himsef had attracted none of the controversy of Berle. Indeed, Sullivan’s show was possibly the most family-friendly variety programme on television. If Sullivan thought Elvis was alright, then perhaps he was. 1956 was, without doubt, the most important year in Elvis Presley’s career. His recordings and television performances within those twelve months have gone down as some of the most important moments in 20th Century cultural history. While he started out the year by simply causing many to raise their eyebrows, just a two-minute performance of Hound Dog on The Milton Berle Show turned opinions from confusion to outrage. What is clear, however, when putting this performance into a wider context of television history (and therefore cultural and social history) is that Elvis very much became a scapegoat for those that disapproved of the changes going on around them, from the new technology of television through to the social acceptance (and even the embracing) of less prudish elements of entertainment that came with the new technology and, most importantly, the arrival of rock ‘n’ roll, which would change popular music forever. Spotlight by Shane Brown. Click here to comment on this review Coming next - Shane Brown's in-depth look at Elvis and The Steve Allen show

EIN Website content © Copyright the Elvis Information Network.

Elvis Presley, Elvis and Graceland are trademarks of Elvis Presley Enterprises. The Elvis Information Network has been running since 1986 and is an EPE officially recognised Elvis fan club.

|

|