|

|

The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley: A Critical History of the Early Recordings By Gary Parker (available now in softcover and Kindle editions) Book Review by Nigel Patterson and Piers Beagley, May 2022 Elvis Presley's clever manipulation of his numerous interests remains one of the music world's great marvels. Presley, with one foot in delta mud and the other in a country hoedown, teamed with Scotty Moore and Bill Black to fuse two distinctly American musical forms -- country and blues -- to form what would come to be known as "rockabilly." (promotion for the book) Gary Parker’s latest book, The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley: A Critical History of the Early Recordings, is part history lesson, part biography, and large part music critique. As its title infers, it is essentially about what Gary Parker (and many others) regard as the most musically creative period of Elvis' career......1954 to 1958 (noting that Elvis’ post-Army studio recordings, particularly the Elvis Is Back and American Sound Studio sessions, are also discussed). The author has a successful background as a writer, contributing to many music magazines and being responsible for the revealing and colorful examination of Jethro Tull in his highly regarded 2018 book, Original Jethro Tull The Glory Years, 1968-1980 (which includes a great passage about the band's reaction to seeing Elvis live in concert during the 1970s). The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley continues Parker’s tradition of well written, thoughtful, and often thought provoking, prose. From the author's provoking Preface, with its intriguing proposition: imagine if Elvis Presley had vanished in November 1955, ‘never to be heard from again’, and there was no Hound Dog, no Jailhouse Rock, no My Baby Left Me, no…., the inclusion of seemingly hundreds of pertinent and instructive observations by those who knew and worked with Elvis, and clever use of song titles for many of the chapter titles, the narrative is lively, conjuring colorful images and imploring reflections by the reader. Parker chronicles Elvis' exposure to, and the impact of, the musically rich environment of the Shake Rag area in Tupelo, the influence of the Presley family's experience of southern gospel, and the vibrant musical-cultural life of Beale Street and Sam Phillips' SUN Records, in Memphis.

It is evident that the author has thoroughly researched and considered his subject matter, the chapters about Elvis in the studio are robust, bringing to life the recording process and offering a well-considered perspective on each recording. With his emphasis being on the creativity and quality of Elvis in the studio in the 1950s, Parker's discourse on the recording process runs deep. He brings the recording studio to life and identifies elements of what makes particular songs, work. Regarding Elvis’ session at RCA Studio B on June 10, 1956:

With A Big Hunk of Love, Parker notes that key to the song's savage power are the driving vocals of the Jordanaires. About Wear My Ring Around Your Neck, the author perceptively offers:

That Parker is not a big fan of what many regard as one of Elvis' best albums, Elvis Is Back, was unexpected, and the defence of his position, thought provoking. The author also discusses, in detail, the role and impact of key personnel, starting with the in-studio creativity of Elvis, Scotty Moore, and Bill Black. In the section ‘Too Hot To Handle’ Parker has an interesting look at how, in 1956, the power of Elvis and rock’n’roll had the mainstream media linking this new teenage excitement to the juvenile delinquency…

The power and excitement of Elvis’ live performances is also examined.

In the stimulating chapter, Pinning Presley Down, the author attempts to identify who the true Elvis was. What he finds is a mosaic of different perceptions around Elvis:

Parker reinforces his point by quoting Johnny Cash:

At another point in the chapter, when considering the role of Colonel Tom Parker in Elvis’ opportunity for musical creativity, the author notes:

The closing paragraph to this chapter is especially powerful and warrants the reader’s close attention and contemplation. In the chapter, Too Much Monkey Business, there is a no-holds barred discussion of the role of Elvis’ guys, the Memphis Mafia:

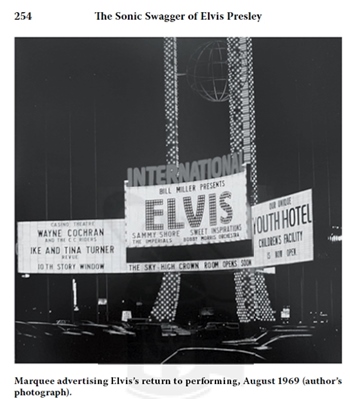

While the bulk of his book is concerned with Elvis' pre-Army recordings, as noted earlier, Parker does also discuss Elvis' post-demob sessions. He draws attention to the musical anaemia associated with Elvis' mid 1960's film soundtrack recordings like Do the Clam and Petunia the Gardener's Daughter, appropriately highlighting the absence of creativity by contrasting them with Top 40 hits of the time such as the Animals’, The House of the Rising Sun and the Rolling Stones’, (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction. As part of Parker’s fine exploration of Elvis’ recording renaissance at the American Sound Studio in 1969, while he acknowledges Elvis’ foray into social commentary with the songs If I Can Dream, and In the Ghetto, he could have also considered his other two, admittedly less apparent, socially reflective recordings from the late 60s, U.S. Male and Clean Up Your Own Back Yard. Regardless, Parker is right in commenting that while In the Ghetto and If I Can Dream ‘hinted at an entirely new career path for Elvis’, they ended up being ‘nothing more than a career curio’. The final two chapters (before the appendices), The Sublimes and Diamonds Amidst the Dross, are not only interesting, but also thought provoking. The sublimes are the 16 songs the author considers to be Elvis' most essential works. They are equally split between SUN and RCA recordings, with EIN’s Piers Beagley finding Doncha’ Think It’s Time, a surprising inclusion. Diamonds Amidst the Dross considers a number of Elvis' recordings that were "diamonds" during what many regard as his "lost" period, musically, in the 1960s, while he was honoring contracts to make his series of "travelogue" films. Among the 11 titles Parker discusses are A Mess of Blues, It Hurts Me, Reconsider Baby, In the Ghetto, and Suspicious Minds. EIN did find it surprising that the author did not identify any post 1969 American Studio recordings that he considered to be of merit. As with any book which includes a listing of the best or most important songs, others will undoubtedly disagree with some on the list. These lists, being a subjective exercise, are always great for eliciting vigorous debate among fans. Throughout The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley there are nuggets of unexpected and enlightening information. For instance, that the author was himself in a band and got to see Elvis live in Vegas in 1969 is not only a surprise but adds gravitas to his credentials for writing the book (he should have mentioned these in his Preface rather than later in the narrative).

Parker notes the seminal importance of the concert at the Overton Park Shell to Elvis’ career, and it was almost revelatory to again read what Sam Phillips told Peter Guralnick for his seminal book, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley:

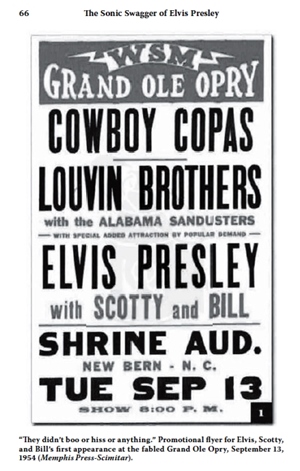

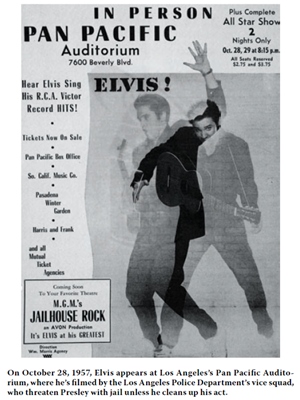

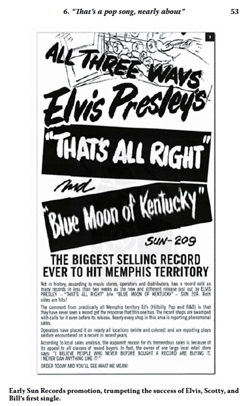

Parker also comments that producer Felton Jarvis was an Elvis tribute artist (ETA) - while Jarvis did have a brief recording career himself, EIN was only aware that any Elvis related connection was his 1959 single, Don’t Knock Elvis, not that he performed as an ETA. And while Elvis may have said to his father, Vernon, that he ‘wasn’t much of a guitar player’, Gary Parker reveals, that on examination, Elvis, while not the most proficient guitarist, was able to adequately handle at least 21 chords. EIN trivia aside: Long-time Australian fans may remember when Elvis was surprisingly ranked in the Top 10 Guitarists Poll in the music (“bible”) magazine, Go-Set, circa 1970. A minor issue in The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley is one or two typographical errors (for example, Marty Lacker cited as Marty Lackner and Rudy Vallee shown as Rudy Valle). The narrative element dominates the book. Its b&w visuals include routine images and film posters (interesting given the author's minimalist coverage of Elvis' films). Having said this, there are several important images:

Also fascinating, are an article on Sam Phillips from the Memphis Commercial Appeal in 1951, and a 1957 article on Elvis from Britain's Melody Maker. The book includes both a detailed index and detailed bibliography (both print and online sources). There are also three appendices which are terrific, informative inclusions: A. The Strange Case of Andreas van Kuijk Verdict: Critical considerations of Elvis' music are always welcome and Gary Parker's The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley, with its erudite and thoughtful narrative, does not disappoint. It is an engaging and stimulating read which offers much for the reader to ponder, often agree with, and occasionally disagree with. Importantly, it convincingly argues the author’s case that, ‘It’s simply indisputable that between the years of 1954 and 1958, Elvis Presley created a body of work that has proven itself imperishable’. The Sonic Swagger of Elvis Presley is one of the best and more important Elvis book releases of 2022!

Review by Nigel Patterson / Piers Beagley.

|

|