|

|

INTERVIEW EIN’s Nigel Patterson recently sat down with Dr. Mark Duffett via the face-to-face magic of Google Hangouts, to discuss Mark’s latest book, Elvis Roots, Image, Comeback, Phenomenon.

Part 1 EIN: Mark, the title of your latest book, is an intriguing one. What can readers expect in Elvis: Roots, Image, Comeback, Phenomenon? MD: It is a book really about Elvis’s image. It has some information about his music, but my objective was to write a book which informed students, teachers and interested fans about Elvis, his phenomenon, and how to interpret it. As part of it, the book addresses a number of the controversies and debates around Elvis. EIN: What was the genesis for the book ? MD: About 10 years ago, Dave Laing, a popular music scholar in the UK was responsible for a series of books called “Icons”, and he didn’t have a book around Elvis. So, when you have a series of books on popular icons that doesn’t include Elvis, there is something wrong. Dave and his colleagues knew that I was an Elvis researcher. They approached me to write the Elvis volume. I was 18 months late with the manuscript. The editor sat on it for four years, then sadly passed away. I got back in contact with the publisher, and we managed to get it out this year. EIN: Were you writing it at the same time as you were writing Counting Down Elvis? MD: Yes, I was. I had started Elvis Roots, Image, Comeback, Phenomenon, before I started on Counting Down Elvis, but for a period I was writing both books simultaneously. By the time I started Counting Down Elvis I had already handed in the manuscript, but I had to do some editing and revision when it was back in the pipeline for publication. EIN: Your two Elvis books are very different in nature, almost diametrically opposed. MD: Yes. In fact, I had to do a lot more “new” research for Counting Down Elvis, as I am not a musicologist. I like to think of the two books as being complementary rather than intrinsically opposed. EIN: Mark, the promotion for your new book includes that it challenges “established perspectives” that others have got wrong. What “established perspectives” have others got wrong? MD: (Laughs) That’s an interesting thing, because sometimes those sort of claims are written as ways to get people interested. I think, as we go through your questions, we will be talking about some of the relevant issues – around Elvis and race, Elvis and consumerism. I can give one example now. A few years ago, there was a piece of writing by Pete Stromberg which said that Elvis fans were essentially a glorification of consumerism. I felt that was nonsense. So, it is one of the themes that I challenge in my new book.

EIN: It is not difficult to understand where Stromberg was coming from, given the way in which Elvis was marketed by both the Colonel and RCA, from the beginning of his meteoric rise. The proliferation of Elvis merchandise was on a scale not previously seen, RCA releasing all five of his Sun singles, and so on. MD: Oh yes, certainly. There is no doubt Elvis is integrated with consumerism and people point to RCA’s marketing of his Having Fun On Stage With Elvis album as a prime example of selling Elvis. There was no music on the album, just snippets of him talking between songs. But they were able to sell large quantities, because people just wanted to be with Elvis. While that part is true, I don’t think that fans are simply all about consumerism; rather, that part is just a means to an end. The role of fans is much more complex. EIN: Mark, you mentioned Elvis and race. This has been a fiercely debated topic, even a divisive one, since Elvis burst on to the international scene back in 1956. In your new book you include a great quote by one of the founding members of The Rolling Stones, Keith Richards. You take his insightful observation that “Elvis turned everybody, into everybody”. But you explore its meaning in the context of Elvis’s unusually integrated sound ripping up genre boundaries. What do you mean by that? MD: Well, there’s a commonly told story that Elvis, at the time, was a “colour blind” musician – that he took the excitement of the music associated with the African-American traditions of gospel and rhythm and blues, and he turned it into something different. He turned it into something that didn’t discriminate in the same way, and – if you look how he topped not only the pop charts but also the R&B and gospel charts – it was something that was universally accepted. The thing about race is that each era brings its own racial politics and concerns, and when we situate Elvis back in his time there was a certain change relating to race that was going on, and that was also happening in the entertainment world. I think that sometimes there is a danger we can read musical changes in a utopian way, but, at the same time, it is evident that with Elvis his music, and performances, popular music became more integrated, and had a more integrated audience, and opened up African-American performers to a wider audience. EIN: Playing devil’s advocate, Elvis wasn’t the first one to do that. For instance, what about Bill Haley & His Comets? MD: Yes certainly. There were other performers doing rock and roll and helping open it up to a wider audience. One of the things we rarely discuss is how the rock and roll narrative represses jazz, where there was also racial mixing. However, I think Elvis was the key protagonist in leading the youth movement and its impact on racial integration that was most prevalent in the 1950s through rock and roll. The acceptance of the vernacular music of American Blues, without prejudice, was a very positive thing and Elvis was central to it happening. Of course, racial change does not happen overnight. In my book I talk about how Elvis opened the doors to other performers. If you have read Todd Rheingold’s book, Dispelling the Myths, it deals with this incredibly well.

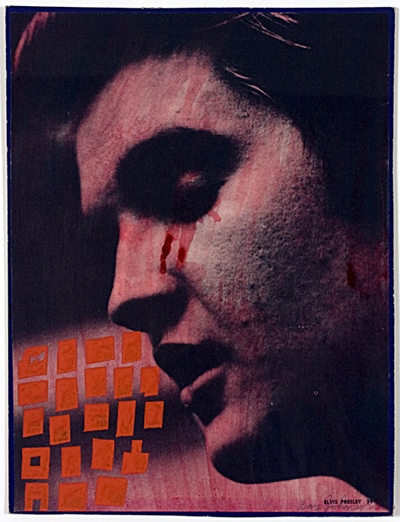

For many decades up until the mid-later 1950s, sheet music had been where the big profits were made. If anything, I think Elvis was part of a new generation where recorded music became dominant. I like the phrase that “Some people make music while some people are music.” To put it another way, Elvis integrated the soul of his music. EIN: Mark, a recurrent and thought-provoking theme in Elvis Roots, Image, Comeback, Phenomenon is that of Elvis and Sigmund Freud’s theory, the Oedipal Complex. What impacts did this have for Elvis and his career? MD: One of the things I try to do in the book is provide an interpretive framework for themes I think were important in fully understanding Elvis and his image. This means ideas and philosophies from the late 1950s period are relevant, such as Freud’s Oedipus Complex and existentialism. They allow you to see things you hadn’t seen before. Some people thought about Elvis Presley immediately from an oedipal perspective. Just as the singer burst across America in the mid-1950s, the pop artist Ray Johnson, for instance, created a picture called “Oedipus (Elvis #1)” .

I think people sometimes misunderstand the Oedipus Complex. There are a number of things in popular culture than reflect oedipal ideas. Film noir is one as is Hitchcock’s Psycho, and more recently, I don’t know if you are aware of the case of Jimmy Saville? EIN: Yes, I am very aware of the Saville case. There is also the photo and account of the time he met Elvis. MD: Indeed. For many years Jimmy Saville was at the centre of UK popular culture. He had an usually close relationship with his mother, one the public knew for many years. I think what was going on is if you look at the Nissen legends of the Blues they were often about social hardship translated in to musical soul, and when the white musicians of rock and roll and what came later in the 1960s and 1970s, that was then translated into a family context. And if you were going to talk about emotions and pain in the family context, the Oedipus Complex was one way to do it: John Lennon also had issues in the family relationship; Johnny Cash is another who also had issues with his father. In Elvis’ case, it all came down to close bonding with his mother. I think this is a social phenomenon that is a connecting point between how people perceive the music and what is going on in ordinary family lives. Returning to what this means around Elvis, you see it come out in publicity about him and what people see as being important. I also think it comes out in plots, in how his Hollywood movies are organised. There is quite often an older woman in the mix. The Lizabeth Scott character in Loving You, and Angela Lansbury in Blue Hawaii, are examples. When we talk about Freud’s theory on the Oedipus Complex we don’t mean it an incestuous way. What we mean is that everyone is to some degree close to their mother because that is the first relationship we have. Elvis did have a close relationship with his mother, but I think that society built on those kind of observations, in building his celebrity image. To some degree Elvis was the beneficiary of that; he capitalised on it. Did you know he actually did a Mother’s Day live performance in the 70’s?

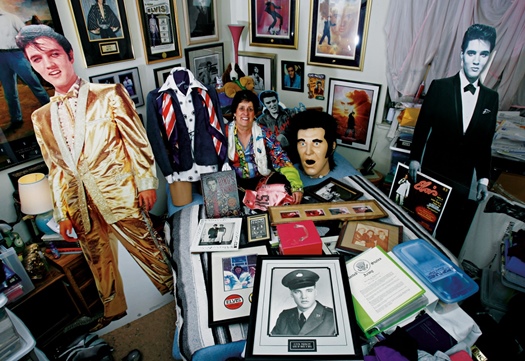

EIN: Yes. The close relationship of Elvis and Gladys is well recorded. In your book you talk about the presence of “good” and “bad” fathers in his life. Could you expand on that? MD: Well, oedipal theory in Freudian terms is that if someone has bonded with their mother as the first major relationship, they may then decide that their father is an obstacle to that relationship and that creates a type of resentment by the child towards the father. That negativity can manifest itself in different ways. I don’t think this is very much to do with Elvis’ actual life, but if we look at Elvis’ celebrity image there are discussions in biographies of Vernon being an inadequate father in various ways, such as he couldn’t provide for his family or he was useless. And then there is the idea that the Colonel was able to come in and act out that idea of the bad father. Obviously, the Colonel realised early on about Elvis’s image, and was able to play upon it and even parody it at certain points, and it became a joke within Elvis’ circle and culture. So, in the book, I was interested in exploring this and it allowed me to explore and explain things in a way that maybe I couldn’t before. The other way to take the Colonel is that he’s just an exploiter; he’s just a parasite. Obviously, there are debates about that. I thought that, for instance, when the Colonel used to call Elvis, “My boy”, it fitted within the Freudian frame, so to speak. So this is not necessarily about the “real Elvis”, but about his celebrity and myth. EIN: Earlier, you mentioned the issue of Elvis and commodification, which is another strong theme in your book. At one point, you discuss the commodification of Elvis in the context of pseudo-religiosity, i.e. in the context of Elvis, the connection, or perceived connection, between religion and consumption. Without going into too much detail, could you expand on this? MD: Elvis and commodification had to be a central theme in the book, as that was always one of the frames where people had talked about him – in terms of the flood of commodities – and it’s really all about commodification. In terms of pseudo-religiosity, one of the things that my colleagues have argued, but I have challenged, is that behind commodification there is some sort of religious practice: what they call pseudo-religiosity. What they argue is that fandom is a type of substitute – a misguided substitute, for religion. I think that is a very negative way to see fandom. It is a complicated issue, because people want to find a language to talk about fandom and sometimes religion becomes a discourse or a way to do that. But I think the dismissive angle, that this is a misguided religion, that it is just a series of religious practices, such as the Candlelight Vigil, Graceland, the writing on the Graceland front wall, etc – people see these as religious practices. And my issue with it is that a lot of discussion about it doesn’t come from talking to Elvis fans. I think it misunderstands both Elvis fans and religion. What is interesting is that there have been more sophisticated variants of the argument. For instance, there is a very good book called The Lyre of Orpheus, by one of my former University of Chester colleagues, Chris Partridge, where he deals with the concept of religiosity. He takes the view that all popular music is religious because it deals with the sacred and the profane. When we look at his examples, there are avant-garde and heavy metal groups making profane music – but with Elvis, Partridge says, fans think he is a saint and he is venerated. It’s always that certain types of fan get chosen to satisfy the argument, but often they are the ones that are quite emotive, or they involve an intense relationship.

EIN: Mark, returning to your idea of the “real Elvis”, you said that Elvis’ personality was largely hidden from public view once he entered the Army, but you also discuss the importance of marketing Elvis’s conservative side. Why was that important? MD: I think there was always some kind of effort to market Elvis’s conservative side. Certainly Sam Phillips was less interested in it, but once Elvis joined RCA, it seems to me that it became a fundamental part of his image. It is important because Elvis always wanted to be a mainstream family entertainer in the mould of Perry Como or Dean Martin. And, in a sense, he achieved that. That’s a short answer to your question. EIN: Continuing the theme, in writing Elvis Roots, Image, Comeback, Phenomenon, did you come any closer to understanding who or what the “real Elvis” is? MD: (Laughs) You know, this is a really complicated question for me because I am not someone who knew Elvis personally. I was seven or eight years old when he died (lol.....I’m giving away my age), and I never met him. So given all this what would it be for me to know the real Elvis? I think that, while you study one individual more and more, and the great thing about Elvis is that there is so much information available about him, you know, absolutely huge amounts of information that we don’t have for other people. That information is often mediated through commercial means or interests, and as we sift through it we have to continually judge how it’s commercially driven, how it’s refracted. I’ve seen some very interested Elvis related books, you are probably familiar with Patrick Lacy’s, Elvis Decoded, where he tries to find the truth about various Elvis “facts.” He ends up putting various versions alongside each other to trying to judge between them, sometimes based on whether they agree. That is a problematic thing, because a majority of them could be wrong. How do we know whether any particular interpretation is correct? Truth is not based on a popularity contest. One account could be factually true, despite all the others disagreeing with it. So I don’t see it necessarily in terms of knowing who was the “real Elvis” but in finding out more about who he was and what has been said about him. And I think in this journey you encounter factual information that you either had forgotten about or you can place in a different way. In a way it’s like unpeeling an onion, you uncover these different layers. I think it is a continual process and through that process you are coming towards an understanding of a real person. But in the same way, with someone as iconic as Elvis, someone who has such a huge audience and has had so many thinks written about him, there is also the issue of the celebrity image, something which I see almost like an art installation. It creates this huge myth of different things, and we sort of see it from our own perspective, and that perspective is informed by a certain amount of information and knowledge. And as we move passed it we see it from a different angle, if you like. EIN: You mentioned that we have this massive amount of information about Elvis. What it is it about him that led to such a volume of information and depth of detail about his life, while for many, if not most, other celebrities, we have significantly less information? MD: Where do I start! On one level, all that I said in my Elvis 100 Finest Songs book, holds true: Elvis was an amazingly talented performer, he could do things with his voice that nobody else could do, and the music was just riveting. And I think those factors taken in the context of him being a professional performer and promoted, that that would generate extreme interest, and it did. And I think the other factor is that Elvis had the story and myth that didn’t get in the way of that. In fact, if anything, it enhanced it. You know: coming from a poor background, being a Southerner, becoming a star in a certain time, being a Hollywood icon – those sort of things, it’s multiple things, including his celebrity image – that came together to engender greater interest in him. EIN: Mark, one final question on the “real Elvis”. How does the idea of the “real Elvis” intersect with Elvis as a commodity and Elvis as an agent of socio-cultural change? MD: Wow, that’s like a real philosophical question. There are a couple of things I can say about it. Back in 1997 I attended a fan club event, I think in Hemsby in the UK, and Charlie Hodge was the special guest. Charlie was recounting his stories, and he said, “My stories are top of the line”. And as I heard that phrase, “top of the line”, I realised this is like a conveyor belt of memories which satisfied his audience, sort of suited the audience as a commodity. I think that answers one of the connection points between the “real Elvis” and “Elvis the commodity”. It is shaped by these different forces, some of which are hagiographic – they want to portray Elvis as a saint – others are kind of realist, and others may be kind of negative, kind of scandalous, maybe for non-fan audiences. Perhaps the “real Elvis” gets lost between these competing interests. All human beings have fallen, and all human beings have come unstuck, so I’m sure there’s much about Elvis that isn’t saintly. But at the same time I’ve ready many, many things about the “real Elvis” that are wonderful. One I read recently, I think it was in a speech by Elvis’s step-brother, Rick Stanley. He said that when Elvis first met his step-brothers at Graceland, and he said to them, “I’ve always wanted younger brothers”. And I thought, wow, Elvis was showing that level of compassion and knowing the right thing to say to make it work. And I’m sure he genuinely meant that. This is an example of a human being who is compassionate, ethical, and caring. And I think, to some degree, we are looking for those things in Elvis...you know, “That’s great, that’s who he was.” And, while that’s who he was, we’ve all got both sides of the equation; if you look at 42 years in the life, of anybody, you’re going to find all sorts of things.

Go HERE for Part 2 of EIN’s intriguing interview with Mark Duffett. In the concluding part Mark traverses a wide range of topical subjects, including the politicisation of Elvis and race; the academic, public and media perception of Elvis today; Elvis fandom compared to the fandom for other celebrities such as the Beatles; the Elvis world in 2020, and his next Elvis book. Interview by Nigel Patterson. About the author: Dr. Mark Duffett is Reader in media and cultural studies at the University of Chester in England. He is widely recognised as an expert on popular music and music fandom, a role cemented by the publication of his book Understanding Fandom (2013). Dr Duffett's PhD thesis was about Elvis Fandom.

|

|