|

|

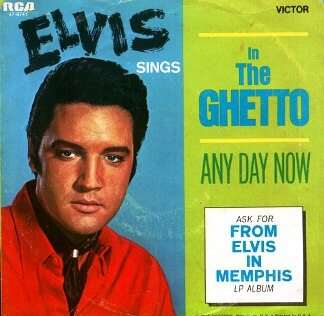

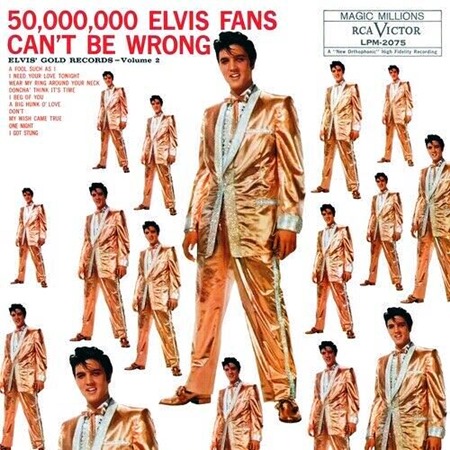

Part 2 of our INTERVIEW - with Mathias Haeussler, author of 'Inventing Elvis: An American Icon in A Cold War World' Interview by Nigel Patterson - 8 December 2020 Read Part 1 of the interview here Part 2 EIN: You’ve touched on this Mathias, but I just had a question here. How important was Elvis as a symbol of American consumerism? MH: Yes, I think it’s a really fundamental part of his image and legacy. Already in the 1950s debates in the US, Elvis’s commercial success is used as a sort of legitimising force of his public presence. So, when you look at, even the most hostile publications, like Life Magazine or the Washington Post, they feel obliged to mention that he’s earned $100,000 for this and that, that he’s sold such and such million records, etc. To some extent, of course, that’s part of the cultural snobbery that Elvis is facing at the time – how can this Memphis truck driver suddenly earn that much money? But there’s also another reading of it, which is to say that, well the market has decided that it accepts Elvis, and you can’t argue against commercial success. And of course, Elvis is somebody who very openly endorses the prevalent consumerist ideology at the time by showcasing his Cadillacs, his fancy outfits, buying Graceland, and so on. So Elvis eventually comes to signify the quintessential American success story, from rags to riches. You have that with the golden Lamé suit, for example, which he doesn’t really like but wears anyway, or with the “50 Million Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong” cover. There’s a great quote from a teenage fan in 1956, who gets asked by a critical journalist why he likes Elvis, and the teenager defends Elvis by saying: “Maybe Elvis is not the best educated person in the world, but he makes a lot of money”. And that, in a sense, really sums up in a nutshell how Elvis’s commercial success helps him eventually become part of the societal consensus in 1950s America. Outside of the United States it’s a different story. But within the US, that’s really a big part of the Elvis legacy and, when you look at Graceland now, that’s what they’re selling. They’re no longer looking at the music, they’re telling the story of the poor boy who got really rich: look at all his cars and his jumpsuits! That’s the narrative that’s really being pushed now.

EIN: Yes. Of course the Colonel wasn’t interested in artistic creativity - he was interested in what can he record that he’s going to appeal to the biggest audience. But do you think Elvis had a sense that the commercialisation of his career may have been impacting upon his creativity? MH: Well, it’s hard to say, because the information we have about Elvis’s personal views is so heavily filtered through memoirs and anecdotes, and he very rarely talked about his views or artistic vision. Maybe you see it in the ’68 special, or maybe in songs like In The Ghetto, but that’s about it really. Elvis, I think, never really overcame a deep-seated inferiority complex. There’s a line in Peter Guralnick’s biography of Sam Phillips, where he quotes Phillips that Elvis had the biggest inferiority complex he’d ever seen in any person, and that rang true to me when I read it. I don’t want to over-psychologize, but it seems like there’s a sort of imposter syndrome about Elvis; “I’ve been so lucky, I’ve made all of this money, and it’s only due to Parker pushing me”, and that sort of thing is maybe also why he remains so deferential to Parker. I think it’s the same with the movies, you know, when he’s asked repeatedly, “So why do you keep making those, let’s face it, crappy movies?” And he usually says, “Well, you know, I have the ambition to become an actor, but I’m not there yet, and you have to learn hard, and if you screw up once, they never give you a second chance and, you know, I have to learn first”, and that sort of thing. EIN: He actually went through a period where he did four or five songs which were actually social commentary songs. Starting with US Male which, while it was tongue in cheek, was poignant, it was having a go at male chauvinism, then there was If I Can Dream, In The Ghetto, and even Clean Up Your Own Backyard, and there’s one other the name of which that just escapes me at the moment. But I find it interesting that in that two year period, he actually was recording songs that reflected a social conscious even though he was somebody who apparently, resisted the recording, or releasing of In the Ghetto, and yet it ended up being one of his biggest hits. And he really identified with If I Can Dream and had no problems with it being released. It is a very strong protest song. MH: Yes that’s his phase, as you say, from ‘66/’67 onwards, when he’s just so fed up with everything that he risks a bit more, and of course after he’s recorded If I Can Dream, he famously says that he’d never record another song that he doesn’t believe in. But that also fades very quickly again, doesn’t it? EIN: It does, unfortunately. MH: And, of course, he doesn’t write his own songs, so, in the ‘60s, it’s what makes a difference to someone like Dylan or even the Beatles, to some extent.

EIN: Speaking of the Beatles and Dylan, one of the main themes in your book is youth culture. Elvis’ role in youth culture was seminal in the 1950s but changed by the ‘60s, as his initial fans were getting older themselves and rock and roll was being replaced by the music of the British invasion. How do you compare his role to that of the Beatles or Dylan? What are the differences between those? MH: Well, it’s sort of like ‘the spirits that I called’ right? Of course, both the Beatles and Dylan are kind of the result of the ‘50s youth culture Elvis helped shape, right? They all adore him. John Lennon in particular, Dylan as well. But then your kids grow up and they go in different ways and, of course, the very essence of youth culture is to kind of carve yourself a niche and to differentiate yourself from your parents’ generation. So in the ‘60s, there’s a new generation coming up, and Elvis is now part of the parent generation. The Beatles and Dylan, I’d say, they take their cues from Elvis, but then they take them in new directions, as part of the cultural renewal and progress in pop culture. There’s, of course, also a big difference because the Beatles and Dylan write their own songs and lyrics, which makes their authorship more directly and immediately visible. I would say that Elvis was as much of a creative artist as the Beatles or Dylan, but the creativity and uniqueness of the Beatles and Dylan is probably more easily graspable if you’re a rock journalist or cultural critic. And, of course, the other thing we’ve touched upon is that the Beatles and Dylan have a much more active political stance on many issues. EIN: Yes, that’s right, and, as you say, it’s very difficult with Elvis to actually work it out, but anyway. Thank you for that. Another one of the things in your book is that Elvis’ popularity in America, but also his popularity overseas, that he was perceived in different ways, and I’m just wondering if you could, sort of, go through those differences, and were there differences, and I say, at a sub-country level, that some non-American countries saw him differently? For instance, say Japan compared to some of the European countries? MH: Absolutely! I mean, that’s one of the most interesting things in the book. Of course, it’s a hugely different story from continent to continent, from country to country. We could go through 150 countries, and in each country, we’d have a slightly different story, how Elvis is framed in those national contexts and I already should apologise for not going into every country in similar depth and detail in the book. I mean, much more could have been said about Australia, for example, or about France or about parts of South America. When you only have a limited number of pages available, you obviously have to prioritise some stories over others, and you have to select your sources, and only have that much time for research. So, apologies for leaving out on so many countries and stories I could have picked out just as easily! EIN: That will be in your follow up book, won’t it? MH: I hope so (laughs). Because you keep reading, and, you know, there’s this new book about Elvis and Asia that’s just come out. Or the interview you’ve had with Jean-Marie Pouzenc about Elvis in France It would’ve been hugely useful for me, and you find out these things afterwards so you think, “Damn, I should’ve had that, you know, about a year or so ago when I was writing Inventing Elvis.” The new one that came out about, or is about to come out, about the LPs in, I think it’s Asia? EIN: Are you referring to From Memphis to Taipeh? MH: Yes, that’s the one. EIN: I believe it’s being released next month. MH: Yes, see that’s something that’s primarily for collectors, but it would have been such a great source for me. Usually, it’s very hard to go into detail about Elvis’s reception in Asia or Japan if you don’t speak the language, so there were also some pragmatic reasons why I couldn’t go into all countries in similar detail. Having said that, I do try to paint a sort of panorama of Elvis around the world during his lifetime. I think the biggest and most obvious context that frames Elvis’s reception globally in the 1950s is the Cold War, which marks some very clear boundaries at first. So in China, for example, Elvis basically isn’t heard of in the 1950s, it’s like he doesn’t even exist!

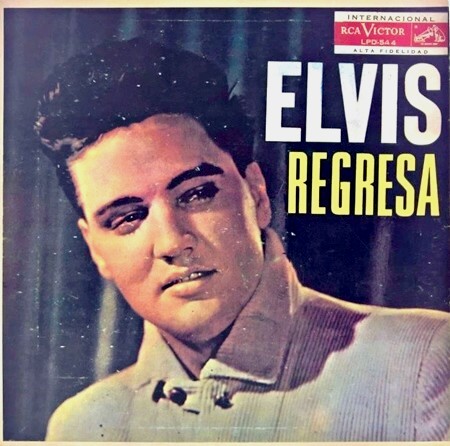

Elvis Regresa - the Cuban Album

In the Soviet Union, he does exist, but he’s very quickly suppressed and banned by the regime, whereas in Japan, a country that’s heavily under US influence in the 1950s, there’s this huge “rockabirii” craze and you even a couple of ‘Japanese Elvises’ like Kazuya Kosaka or Masaaaki Hirao. A really interesting story is Cuba, where, before the revolution, Elvis is very popular and RCA even has its own press, but after the revolution, the Castro regime eventually cracks down on Elvis, and they’re no longer allowed to sell Elvis LPs, radios stop playing Elvis music, and so on. So, this is where you can see a rather direct impact of the Cold War on Elvis’s reception. Europe is an interesting case too. Because initially, in both Western and Eastern Europe, you have very similar dynamics to the US – Elvis as part of an emerging youth culture that is resisted by the establishment. But it then gets politicized in very different ways: he’s banned in the East, but grudgingly accepted in the West as part of an emerging US-style consumerist entertainment culture. EIN: Ok, very interesting. The 1970s, the “me” decade. In the context of your book, where is Elvis, when it comes to the ‘70s? MH: Yes, the ‘70s. That was the most challenging chapter I have to say, because, first of all, you have so much more material on Elvis in the ‘70s than you have on the ‘50s. But, also, Elvis operates in a cultural environment that is much bigger and much more diverse than in the 1950s. So, two things. First, I think it’s important that Elvis’s comeback takes place amidst a bigger nostalgia wave in the late 1960s. There’s this retro trend – hula-hoops, Sha Na Na, and all that – and Elvis, although he doesn’t want that himself, becomes part of it. I think a lot of it has to do with this sense of uncertainty and crises hanging over the country – the assassination of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, Vietnam, Watergate, the oil shock. And, in that cultural climate, Elvis provides a sort of emotional refuge from the past. In that troubled decade, Elvis comes back as a sort of generational memory, as a nostalgic anchor for many of his former fans. He offers an opportunity to visit the allegedly ‘simpler times’ of their youth; a sot of nostalgic solace. I think that actually causes quite a bit of frustration for Elvis himself, because I think he’s very eager to reinvent himself as a contemporary artist at the time: he records amazing new material, he puts up a band that represents the very best of American music, and he puts up a great show. He’s not a retro act at all! But his reception by the press, and by some of his fans as well, is deeply moulded in that 1950s’ nostalgia. I think there’s a bit of a tension between what Elvis wants to do as an artist and how he’s perceived by the wider public. And it’s also important because it reconfigures the memory of the 1950s Elvis. Suddenly, people say, “Oh god, look at the ‘50s. It was all so innocent back then, a little kid just shook his hips a bit and we all went crazy. Look what mess we’re in now”. Which, of course, totally belittles Elvis’s actual cultural impact in the 1950s, and the much bigger tensions over race, class, and gender that crystallized in his persona back then. As regards the “me” decade, well, what Tom Wolfe argues in his famous essay in 1976 is that Americans were seeking refuge from the political and economic upheavals of their times through radical self-fulfilment: in self-help books, in spiritual things, maybe in their careers, in solipsism. And I think Elvis, in a sense, fits the bill here too. He really seemed kind of lost for much of the ‘70s, as many others were too. So I think Elvis fits that sort of collective soul searching that was going on the 1970s. When Elvis died, Lester Bangs wrote in his Village Voice eulogy that Elvis was perhaps the greatest solipsist of all. And I really like that. There’s a reading of Elvis that, you know, the super rebellious ‘50s’ figure then turns into this embodiment of grass roots bible belt conservatism in the 1970s, but I think that’s way too simplistic. Elvis wasn’t an all-out rebel in the 1950s, but he also wasn’t the super-conservative dude in the ‘70s.

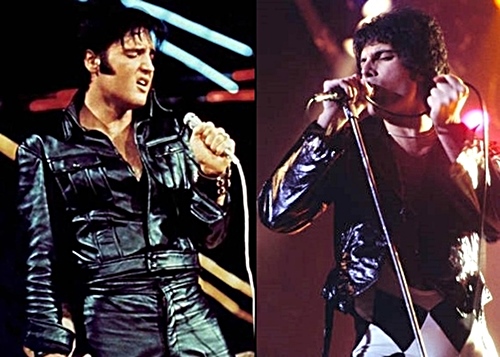

EIN: That’s very interesting, thank you. How would you characterise Elvis’ ongoing presence, since he died in 1977? MH: Well, I mean, historians……for me Elvis actually died in 1977, and that’s it. So, I don’t look too much into his rather peculiar cultural afterlife. But I would say that many of the bigger debates that were being fought around Elvis during his lifetime – race, class, gender - they still resonate in his image today.. Commercialism, consumerism, still a big issue. These bigger issues are still being negotiated in American society all the time, and Elvis still reflects those issues. But the difference is, and that’s the historian coming in again, that Elvis is no longer there. So he can no longer influence how people see him; he no longer has authorship and agency. He’s like a post-modern cultural construct that floats around, and people project all sorts of things onto him. EIN: So you don’t see Elvis tribute artists, sort of, having a huge role in propagation of Elvis? MH: I think it used to be bigger because there used to be more of them, at least that’s my anecdotal impression… I mean, the impersonators, it’s almost a cliché in itself. When you mention Elvis to people who don’t care about Elvis, who have never heard any of his songs or something like that, the things you typically get is jumpsuits, sunglasses, hip shaking, Las Vegas – and tribute artists. That seems to be the collective public memory of Elvis in a sense, which is a shame, because there’s so much more. But I do think that tribute artists played a part in shaping that particular image. And, of course, it’s something that happens even in things like New Girl, the Netflix series, where Zooey Deschanel performs as Elvis in a jumpsuit during a wedding. What I find interesting too, that’s probably a question I would ask you: why is it that the ‘70s Elvis seems to be so much more popular than the ‘50s Elvis, both amongst fans and in the public memory? I mean, is it simply because there’s just more material there? More images, more soundboard recordings, and what not? EIN: My view is the 1970s is also closer in time. There was also a bigger audience for it back then and, here’s the thing. If you look at the tribute artists, I mean, 90% of them do the ‘70s’ jumpsuit. So all these things are reinforcing that. And I guess that sort of Vegas type thing has still been with us in some form. But my question to you would be, is, look, what always impressed me about Elvis tribute artists is, you compare them to any other artist, even the Beatles, Michael Jackson, David Bowie, there is just a 100 times as many Elvis tribute artists as for the Beatles or Michael Jackson. Why is that? MH: I have no idea (laughs). I mean, I was wondering that myself. Maybe because Elvis was in such complete control of his image? After all, the public got very little: you get the concerts, you get like five interviews, you get the music, you get the movies, that’s about it. I mean, there’s not much else apart from his cultural products. Elvis the person remained this sort of mystery throughout his lifetime, you know, hiding away in Graceland, and all you really had was the public image. Maybe it’s also because he was the first all-round modern-day celebrity. I mean, Elvis really became his own personal brand, and maybe that plays a part too. Maybe it’s also the crass commercialisation of his image, with all the merch featuring his picture, maybe that plays a role. It’s very hard, it’s very hard to say. Maybe also because he never appeared outside of the United States, so people are looking for a sort of substitute. That really is one of the most amazing things: Elvis is a global icon, people around the world recognise Elvis, but he never actually performed outside of the United States, except for those few shows in Canada. He’s been a medial construction in most parts of the world, and there’s been no sort of first-hand experience, ever. EIN: I could probably debate that with you, given the preponderance of the tribute artists seem to be in the US anyway. Although, look, I’m in Canberra, which is the national capital. We’ve got, we’ve now got a population of 400,000, but, at one stage, we had six different Elvis impersonators - in Canberra. Yes, ok? MH: Yes. EIN: We don’t any more. We’ve probably got one or two. They don’t do much, as you said, it’s just the demand for that is getting less and less. But, I mean, you look at the commercialisation, I mean the commercialisation of the Beatles probably was on an equal, if not a greater level than Elvis and, yet, we’ve got this, I mean there’s, you know, half a dozen maybe tribute Beatles’ groups that I can think of. MH: And, yes, there’s four of them, which kind of complicates things. EIN: Yes, true. MH: That may be a problem. But, also, Elton John maybe. Elton John of course is still alive and he himself dressed up in all sorts of ways, so he’s harder to imitate in a sense. Same with David Bowie. I mean, they’re both much more self-conscious, they’re much more deliberate in how they create their stage personalities. EIN: Yes, although, I’ve got to say, I mean, we have a very, and he’s very good too, I’ve seen him. We have two in Australia. One who does Neil Diamond, I’ve forgotten his name, and the other one is a guy called Elton Jack, who does Elton John, who’s very good. But one of the interesting things, and this goes back 10 or 15 years, I was up on holidays on the Gold Coast, at one of the casinos there, they had an entertainer who was doing one half of the show Elvis, and the other half Freddie Mercury.

MH: Aah, yes, I mean, Freddie Mercury, yes. I can see that. hey would, kind of, lend themselves to impersonation. EIN: Yes, and I have to say, I thought the Freddie Mercury...... I mean he was very good as Elvis, but I’d have to say, I probably enjoyed the Freddie Mercury more. I don’t know if it’s because I’ve seen so many Elvis tribute artists, and Freddie Mercury was a breath of fresh air..... but he was very good. But you are right, the numbers are declining, but there still seems to be a lot of tribute artists around, although I suspect when that initial cohort of Elvis fans passes on, there obviously will be less and less of them. I mean, the interesting thing with Elvis is that he has second large cohort of fans, like myself, that weren’t there in the ‘50s, and became fans in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. So it’s a while before we all go.....I hope. MH: But he doesn’t really tap into the contemporary youth market as much right now, even though EPE is trying. On the other hand, with the Beatles, maybe this is just my personal experience, but you do come across Yesterday, Let It Be, Hey Jude all the time by singing it at school, by listening to it on radio. Much less Elvis there, and it’s an interesting question why. EIN: That’s a very good point. MH: And there’s also a stigma, I think. In the US, in particular. I think, he’s still, after all those years, he’s still being associated with that sort of hillbilly image, and I think that plays a part too. Of course, Albert Goldman, you know, all the things how Elvis was sort of written down in the ‘80s, that contributed to that too. And, I mean, it’s maybe no coincidence that, you know, Trump out of all presidents, gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. I think, that was interesting. EIN: I agree with you that there still is that stigma. I’ve always been intrigued about this issue. I mean, part of it is that he didn’t write his own music, and that in the ‘70s he became, in some respects, a caricature of himself. But, yet, he is such a global phenomenon. He is strong in western countries, in eastern countries, in Africa, South America. There is just a body of interest in Elvis. Regardless of that bible belt conservatism, or whatever. MH: EPE’s, or rather the Authentic Brand Group’s, strategy seems to be to sell Elvis’ life story, the image – rather than the music. They are really trying to push that narrative that Elvis is a kind of American folk hero. My strategy would be the exact opposite. As I said earlier, how I became a fan was largely due to the professionalization of Elvis’s catalogue in the late 1990s and early 2000s. I was very lucky to become a fan at the time when I could buy the Essential Masters 1950s box set. I could read the two volume Guralnick biographies, Careless Love had just come out, and of course there was the Internet where I could find all sorts of information. Had I become a fan in the 80s, I probably would have bought a Golden Records album with a few film songs, and then maybe read the Albert Goldman book, and I would have thought “Ewww!”. I think Elvis really lost a generation there in the 1980s.

EIN: I suspect you would have read the Dave Marsh book in the 80s rather than Goldman. MH: I would hope so! I hope that would have been more to my taste (laughing). Anyway, my take is, let’s push Elvis’ art, let’s push his music. Get the good stuff out to the people again. There are signs they’re doing this again with some of the new releases. EIN: Mathias, thank you! You have made a really important point. EIN: Do you have plans for another Elvis related book? MH: I really wish. Inventing Elvis was a labor of love. I originally planned to write only a little article, until I realised I had too much material. For the time being I need to re-focus my work on slightly different topics. But I do have a chapter coming out in Mark Duffett’s Oxford University Press volume due out in 2021. I think that book is going to be a milestone for academic literature on Elvis. EIN: EIN knows Mark is a very good friend of yours. Now that he has two discrete books out on Elvis don’t you need to keep pace? MH: The good thing is that our works are very complementary! Mark’s work is a great piece of cultural studies, which really pushes the interpretation of Elvis to new levels. Mine is slightly more historically-grounded, I suppose. So if you read our books in tandem, it gives you two slightly different perspectives, but perspectives that complement each other very well. I am also working on an article around Elvis in 1950s Europe with another fellow academic, Bertel Nygaard. EIN: Bertel also published an Elvis book recently? MH: Yes, he did – Elvis I Danmark. Unfortunately, it’s in Danish and I don’t speak Danish. But it is about Elvis’ impact in Denmark and his role as a cultural icon. EIN: Mathias, the final question. Is there anything else you would like to say to EIN readers? MH: Firstly, I’d say a big thank you to anyone who has managed to read this very long interview all the way through! Also, I would like to say that while I was doing my research, I really came to admire the encyclopaedic knowledge of many Elvis fans even more than I already had. These fans really have the best knowledge of Elvis, of specific details - you know, split take 23 of a particular movie song he recorded and the like. Regardless of how many books there are, fans are really pivotal in keeping his memory and legacy alive. So I’d say keep up the good work! EIN: Mathias, a supplementary question. Assuming academics are still considering Elvis in 100 years’ time, will they be examining his music or his socio-cultural impact, or both? MH: Both, of course! As historians, we address the past in order to ask questions about the present: “How did we get where we are now?” So, in a hundred years’ time, if you ask a music historian about Elvis, you’d get an answer about Elvis’s music. But if you ask about the origins of the sexual revolution, you’d probably get a answer about Elvis’s socio-cultural impact. I think Elvis is equally important in both regards. EIN: Mathias, thank you very much. It has been a great pleasure talking with you today about such interesting themes around Elvis.

Read EIN’s review of Inventing Elvis: An American Icon in A Cold War World Read Part 1 of the interview here Interview by Nigel Patterson.

|

|