|

|

INTERVIEW - with Mathias Haeussler, author of 'Inventing Elvis: An American Icon in A Cold War World' Interview conducted by Nigel Patterson via Zoom technology on 8 December 2020 In part 1 of a fascinating interview, Mathias Haeussler discusses a wide range of topics including:

EIN: Please tell us about Mathias Haeussler?

EIN: To consider a book about Elvis in the Cold War context. There must have been a number of key drivers. What were they? MH: Absolutely. The short answer is that I have been a fan since 2001-2002. It was really a great time to become a fan as you had all of the Essential Masters box sets, particularly the 50s Masters, and the Guralnick books. The book was really an excuse to pursue my hobby in an academic context, to combine pleasure with work. The longer answer as to what brought me to the precise topic is that my first visit to Graceland was in 2010 and I did the tour…. back then you still had the jumpsuits and the racquetball court and when I was taking in the jumpsuit exhibition, I saw these certificates in a corner including one from Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of State, thanking Elvis for his contribution to the Cold War. And that really got me thinking, what could Elvis have had to do with the Cold War? So I started reading some books on Elvis and history; books about the 1950s and 1960s and I didn’t manage to find a satisfactory answer. But the issue stayed in the back of my mind and then a few years later I decided to write that book myself.

EIN: That is very interesting. What exactly did the certificate say? MH: I found out later that in fact anyone who had enlisted and undertaken military service during the Cold War period could request a certificate by asking the Department of Defence that their service be recognised. So the certificate said something like ‘This is to recognise the service of Elvis Aaron Presley during the Cold War’. But it did its job and got me thinking about the things that I’ve written about in my book. EIN: Mathias, many Elvis fans will be surprised that you have written a book about Elvis and Cold War politics. While EIN realises that relationship is complex, can you briefly outline how Elvis and the Cold War are congruent. MH: I am not sure “congruent” necessarily works for me - it is a very complex relationship. The two historical phenomena – the Elvis phenomenon and the Cold War - certainly happen at the same time, they overlap, and there are countless connections, but I wouldn’t argue they are dependent on each other. I wouldn’t say Elvis rose to prominence because of the Cold War context as that would be taking it too far. However, there are certainly numerous interrelations. In understanding what I mean, I should probably first define what I mean by the ‘Cold War’. It was certainly a military-political-economic contest, but it also had a deep cultural dimension; it was also about very different ways of seeing the world – the customs, values, and perceptions of different societies and different groups of people. There was competition about which value system delivers best for the people, capitalism or communism. And that question also played out everyday life, precisely at the time that Elvis emerges in the 1950s: the time of the Korean War, debates around the future of Germany, the Atomic Bomb, etc. Within the US too, it is a time of particularly acute self-reflection – it’s just after McCarthyism and there are a lot of debates about communist infiltration. So, there was a lot of self- questioning: “Who are we as the people of the United States?”, “What do we believe in, what are our values?”, “What do we want to project to the wider world?” And Elvis emerges at this time. It doesn’t necessarily mean there was a causal connection, but it shapes how he was perceived and received, how people gave meaning to Elvis. He became part of the question: What is America, what should it be? But also: What is it not? For large parts of the establishment like journalists from the Washington Post, the New York Times, etc, they clearly think that Elvis should not be part of what they want the United States to be. Whereas Elvis’ fans of course think that he is very much part of their imagined America. That conflict turns Elvis into a negotiating platform for all sorts of issues, including class, race, gender, and so on.

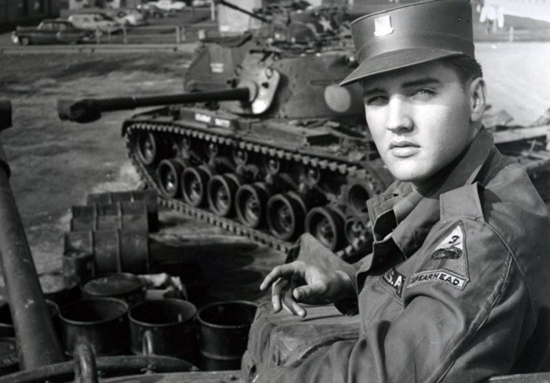

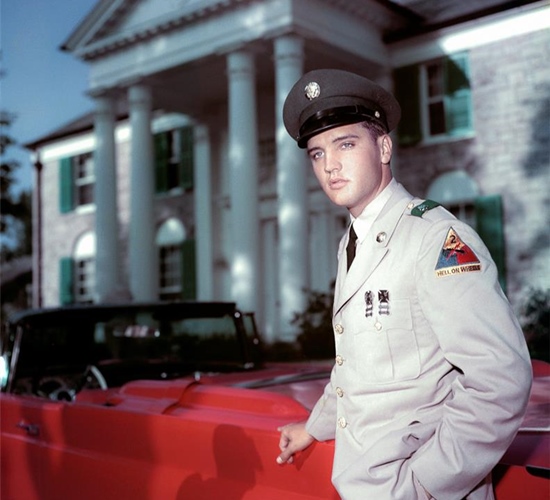

EIN: Given what you have outlined, how active were American authorities in using Elvis as a tool during the Cold War, particularly in the 50s? MH: The 50s had been a time of enormous American expansion outside the United States. There was military expansion in deploying troops in many parts of the world, political, economic and cultural expansion, particularly in Western Europe. And there was a big propaganda machine building up in the State Department, euphemistically called the United States Information Agency, which was designed to project images of the good life in the United States. But they actually stay well clear of Elvis, because they think he doesn’t project what is great about the United States. In fact, they see him as a threat to the American youth, inciting screaming teenage girls and rowdy teenagers. So, they don’t like Elvis at all, they’re thinking he’s corrupting our teenagers, he is a bad influence, and should not be promoted abroad. So, Elvis really travels around the world through non-governmental channels in the 1950s: through RCA which is expanding its global music distribution at the time, through overseas journalists who read about Elvis in American newspapers, through Hollywood companies like Paramount a bit later on –it’s an informal sort of spread. Elvis is not pushed by the government, he is pushed in spite of the government’s resistance against him. EIN: By the 1960s, Elvis’ image as an anti-establishment rock and roll rebel was displaced by a new image of him as the “patriotic, boy next door”, and of course his “travelogue” films. How did these changes impact Elvis’ role in youth culture and American propaganda? MH: The Army years really are the game changer. Elvis’s image starts to morph a bit earlier, I think, but the Army years are the real turning point. Within the US, it paints a picture of Elvis as “one of us”, “he’s a boy doing his duty”, he’s not better than anybody else, he doesn’t get preferential treatment, he’s a patriotic guy. That image really rehabilitates Elvis in the eyes of those groups that initially resisted him. When Elvis comes back from Germany, there’s a big eulogy on him in Congress, he is awarded a medal in Tennessee, and outside of the United States, he now stands as a symbol of this imagined Cold War community of the so-called West.. With regards to Elvis’ films, I think they reflected the rather one-dimensional image of what early 1960s US propaganda wanted to project: individual freedom, a happy-go-lucky guy that achieves success, sunshine, everyone has a nice car, a refrigerator, etc. All those signs of capitalist America are very prevalent in Elvis’ Hollywood movies. Elvis’ popularity grew significantly around the glove in the early 1960s, particularly in parts of Asia such as Hong Kong and Singapore. But Elvis’ films aren’t formally deployed by the US Information Agency, they rather complement its work and the images it wants to project. At least I wasn’t able to find any evidence that the Information Agency systematically used Elvis to promote American ideals. The film companies, Paramount, MGM, etc, that he worked with, all had offices internationally, and through his movies they sent out the images that the propaganda machine would have done anyway. There was no need for the government or State Department to intervene – they complemented each other quite well. Even in the 1950s, Paramount already promoted Elvis being drafted into the Army and going to serve in Germany. Paramount was really on the ball, inviting all the journalists, sending out the footage around the world immediately. When I was researching my book, I looked at the Hal Wallis archive files and it was really amazing how much effort Paramount put into promoting Elvis’s military at the time. Colonel Parker obviously pushed them quite a bit, but they really were a perfect PR agency for the army.

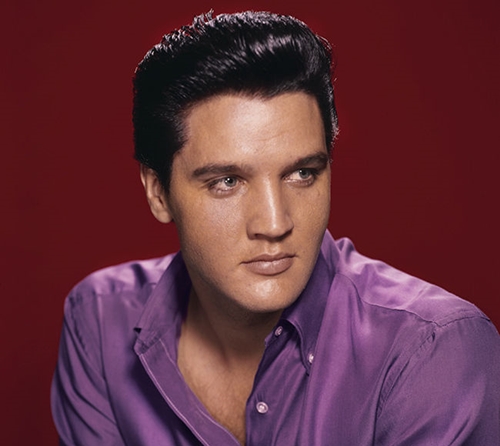

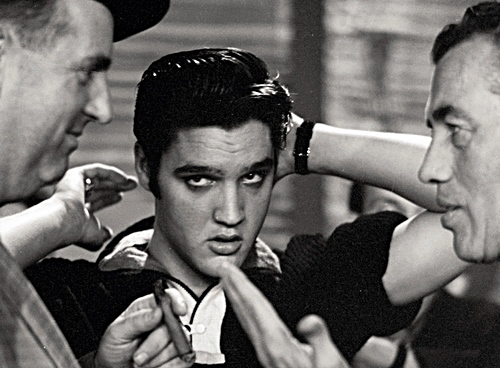

EIN: Mathias, fundamental to your narrative is that Elvis existed in a popular culture environment which was very different to the one that preceded him. Please tell us about this. MH: That is a very complex question. I think there is a difference between mass culture and popular culture. Mass culture, which was around since at least the 19th century with fun fairs and early 20th century with radio and movies, there were stars and celebrities back then. But in what we call “popular culture”, there is another element in the sense that its consumers take a much more active role. They are not merely passive recipients; they use and utilize pop culture to make claims and statements about their tastes and identity. The 1950s teenagers, Elvis’s early fans, are a good example. They push their tastes for Elvis and rock ‘n’ roll in spite of the initial resistance by the cultural establishment and the mainstream entertainment industry at the time. So, audiences use popular culture to make their voice heard, by going to concerts, by buying records they want, and by screaming at stars like Elvis that they are not supposed to be screaming at. In due course, people start to realize that this is of course also a really lucrative market, given the explosion of the teenagers. In the 1950s, you have this group of young people between childhood and full adulthood, who spent much more time in education and also have much more money to spend than ever before. That market power meant teenagers could actually push things onto the market. Look at TV stations. The executives at CBS, NBC and ABC, they all thought Elvis was untalented, obscene and shouldn’t be seen, but when they do show him nonetheless they get record numbers and eventually become desperate to hire him. Even Ed Sullivan, who is the most famous example, said “I’m never going to have Elvis on my show” and then Steve Allen beats him in the ratings and then two weeks later, he’s suddenly inviting Elvis. This was a previously disenfranchised audience pushing its taste into a mass market and that was something that hadn’t really happened before. EIN: If Elvis hadn’t been there, would that change have happened as quickly? MH: That’s a tricky question. Individual agency versus bigger structural forces. Some of these changes would likely have happened anyway, and Elvis certainly didn’t single-handedly trigger all of them. But he’s certainly a catalyst, and Elvis doesn’t get there simply by accident. He gets into his unique position because he’s enormously talented as a singer and performer; there’s real artistic substance behind the hype. And he unites several trends: the “teenage rebel figure” from Hollywood movies meets the rock ‘n’ roll hype. I also think that it’s important that Elvis becomes this multi-media icon who works on several platforms: music, television, movies. He’s not just a singer, he’s a star on all sorts of platforms. He has the whole package – and gets marketed as a teenage star, rather than just a rock ‘n’ roll singer. One of my favourite articles about Elvis I from the Memphis Press Scimitar and written by Robert Johnson in early 1955, I think. Johnson says ‘Elvis, he’s not just a musician, he also has the looks, he has the girls’ etc., and he ends up by saying: ‘Elvis sells!’ And that’s really key to the Elvis hype in 1956. Elvis sells – on every platform. EIN: In your book, you also talk about Americans having a deep-seated fear of communist infiltration during the Cold War. How did Elvis become part of this? MH: Well, Elvis emerges at this time in the 1950s when there was this acute self-reflection over what is American identity and what is not, and there are all those witch hunts of McCarthyism, etc. And that offers Elvis’ opponents an opportunity to use anti-communism to denounce him as a threat to the innocent American youth, corrupting their morale, destroying the religious and moral fabric of the US – all those sorts of things. Those narratives were something his opponents could very readily use as a weapon against him, and at the same time re-asserting their own cultural hegemony and authority. It was one tool in that bigger debate, but to be fair I don’t think many people seriously thought Elvis was communist. I’m not sure it really worked at all. EIN: How did Elvis’ opponents justify their actions in the 1950s when Elvis returned from the Army? Wouldn’t they have had to do a 180 degree turn? MH: Yes, pretty much! The ‘rebel’ story is largely over by 1960. Parker cleverly marketed Elvis while he was in the army with features in Life magazine etc, which project the image of him as only doing his duty, being a great soldier, and he’s just an all-round great guy. This meant that those who had initially opposed him couldn’t really project him as anti-American any longer. To save face, they could portray it as “The Army has turned Elvis around”, which obviously wasn’t true: Elvis was less of a rebel in the 50s than he was often made out to be, and he was also less of a conformist in the 1960s and 1970s than he is commonly seen these days. But it is a narrative that is pushed once he gets out of the Army.

EIN: Given the evolution of the Cold War and attitudes in America, Elvis was initially perceived by the establishment as being a rebel, etc. By the time he returned from the Army that had changed. Had broader attitudes changed in American society or was it that after demonstrating his patriotism, Elvis was seen as the good old boy, the boy next door, the boy who would go to war for his country? MH: Well I’m not sure how much general attitudes had changed by the early 1960s. But, as you say, the ‘good boy next door’ narrative also worked to bracket out some of the more contested issues about Elvis. Let’s take the three areas that I focus on, and that many other people focus on too, class, race and gender. By 1960, all of these issues still resonate with Elvis, but they’re no longer in the foreground, and the question is why? There are different answers to each of them. I think with gender and sex, I’d say, yes, there is a change. I mean, there’s the sexual revolution that comes in the 60s. The attitudes are much looser already in 1960, than they were in ‘56, and you see this in the movies too. But with race and class, I think many of Elvis 1960s movies just ignore these aspects – which had been so important to his earlier popularity – they ignore these aspects altogether, and they sort of portray Elvis as this one-dimensional Horatio Alger guy. EIN: Yes, and they still stick today in a lot of respects, too. The gender issue, even though it’s not seminal to your book, is an interesting one because there have been a number of academic publications around Elvis and gender, particularly for his wearing of mascara, etc, and how he appealed to males and females, and particularly to the gay community. While it wasn’t seminal to what you were researching, did you form a view on the issue? MH: Well, I mean, I haven’t come across any sort of archival, written down sources, simply because that discourse is something that’s completely suppressed in 1950s’ America. I do think Elvis is a bit of a gender-bender in the 1950s by the way he dresses, as you said, he puts on mascara, he puts on make up, etc. And when you look at local newspapers when they report on Elvis coming to town, they usually comment on that, but in a very coded way, you know, like, “he’s flashy”, “he’s dressed in pink”, that sort of thing. So there’s an underlying discourse, but it’s really not articulated explicitly. As regards Elvis and female sexuality in the 1950s more generally, I think, Elvis is a bit of a storm in a teacup. I mean, of course, the early shows are really uninhibited, the girls are letting loose, screaming, they tear his clothes off, and so on. But then they all go home for dinner, maybe have a milkshake, go to prom night, get married, you know. So Elvis’ concerts are a relatively safe outlet for sexual pressure, in a sense. It is a rebellion, but it is a rebellion within those wider constraints of 1950s’ America. It may have set the ball rolling, but it does not upset bigger societal structures as such. The structures actually contain that rebellion for the time being. Although, of course, in the long run, Elvis may have pushed boundaries quite a bit.

EIN: It’s interesting, on those boundaries, and the gay issue, as an avid Elvis book collector as far as I can ascertain, the rarest Elvis book in the world seems to be a one off, and it was part of a set of 21 gay books which was published in 1957 or 1958, and his volume was called Miss Elvis Presley. They were all hand drawn and from what I’ve seen, the drawings are very explicit - Elvis with other young men. MH: Oh right, no I’ve never come across this. That’s very interesting. EIN: From other things I have read about this, about the affinity of the gay community with Elvis, -that’s it’s a very interesting issue. MH: Yes, totally. And I’d be curious to see the Miss Elvis Presley book. EIN: As I said, it appears that there’s only one, and the set is available from, I can’t remember the name of the bookstore, but it can be found by searching abebooks.com. I ran a small news item about it on EIN a few years ago. The bookstore in America that has it, has all 20 volumes in the set. If you’ve got a cool $45,000 American, you can buy the set. MH: Not quite $45,000, I’m afraid! EIN: Mathias, one of the other interesting themes in Inventing Elvis, is you talk about Elvis’ sexualised on stage performances, his gyrations, etc, and you make the point that that you can look at this two ways. One that those performances helped deliver America from that conservatism, from the Eisenhower years, but you could also look at it another way, that in fact it ended up reinforcing conservative and patriarchal gender roles. I think a lot of people would say the former, that it freed America, but what do you consider is the argument for the latter, that it actually reinforced conservatism, if you like? MH: Well, partly what I just said about the storm in a teacup. Elvis, after all, offers a relatively safe outlet for all the sort of the pressures of 1950s America, the rigid moral codes, nuclear anxiety, all that. So, you go to an Elvis concert, you let loose, and then you go home. But it doesn’t really upset the bigger structures of society as such. And, in a way, that can actually reinforce those bigger structures: you can let off some steam from the pressure cooker, but it doesn’t actually explode.

EIN: Picking up on that storm in a teacup thing, one of the things I noticed, I thought the most rigid and most profuse opposition to Elvis in the ‘50s tended to come from the religious groups, far right religious groups. I mean, they were the ones that, you know, wanted to burn his records or break his records, etc. My view, having studied religion myself at university, is it’s very hard to change the views of strident religious believers, and it just seems to me that between ‘58, I mean, the Ed Sullivan, I mean I agree with the army as a turning point, Ed Sullivan Show was also an important point when, you know, Ed Sullivan said, “he’s a fine, decent boy”, and all of that, but to turn around the very strident attitudes of, particularly, right wing religion, it just seemed to me it happened very quickly. MH: Yes, I’d definitely agree that the change in Elvis’s image comes earlier. I think by the time Elvis is drafted, that story has already been played out. It’s partly because of the acceptance by Sullivan, as you say. But also the performances themselves: On Sullivan, I think Elvis seems quite staged and choreographed, he sings Peace in the Valley and Love Me Tender, and when he does Hound Dog its like ‘la-de-da’ for 50 seconds, so he in a sense almost disassociates himself from that tune already (as he then would in the 1970s concerts). And, of course, it also helps that he stops performing live almost completely in 1957, and that Parker takes even closer control over Elvis’s public image. The 1950s movies – Loving You in particular – can also be read as a sort of attempt to whitewash Elvis’s life story for mainstream America. He’s still a sort of country boy hillbilly character, but he’s no longer, you know, the really rural poor Southerner like he actually was. The whole stage moves are also really restrained, there’s no allusion whatsoever to the African-American roots of rock ‘n’ roll, and then towards the end, you have this super-patriotic speech to the mayors of Freegate about liberty and American values and so on. That is quite a conscious attempt, I think, to make Elvis’s legacy fit into larger narratives of the so-called American way of life while sidelining the more contentious issues – but I may be over interpreting the movie. EIN: Right, no I agree with you, although I think probably the problem with Loving You being released in 1957, it was too soon. MH: True. EIN: And the race issue was too powerful back then and, obviously, Parker would not have wanted anything about race to be introduced. MH: Yes, but I mean the interesting thing with Elvis is that he is one of the very few white rock and rollers who openly and repeatedly acknowledges his debts to African-American culture in his interviews, and when he attends the WDIA fundraiser in Memphis, etc. But yeah, Parker obviously doesn’t want that at all, and Elvis obviously concedes on that point by and large. I mean, King Creole in the 1950s and Flaming Star somewhat allude to the racial dimension of Elvis’s image, but that’s pretty much it for the 1960s. EIN: That issue of Elvis and racism has been a continual undercurrent and theme that comes up every few years, and there’s so many, particularly black Americans that think Elvis was racist because of certain comments that were published. MH: Yes, the famous ‘shoe shine’ incident. The best book on Elvis and race is Michael Bertrand’s, Race Rock and Elvis, I think, so I’d defer to him on those points. EIN: Yes, that is a very good book. MH: Obviously, he’s an historian - we fellow historians stick together (laughs). Really, I think that’s the best book on the topic by far! EIN: Yes, well we won’t hold that against you (laughing). But, no, it’s an excellent book. It is one of my favourites too.

In the concluding part to his interview, Professor Haeussler discusses:

The concluding part will be published on EIN next week. Read EIN’s review of Inventing Elvis: An American Icon in A Cold War World

Interview by Nigel Patterson.

|

|