|

|

Eric Wolfson is currently writing the first Elvis inclusion in the popular Bloomsbury 33 1/3 series of music analyses, From Elvis in Memphis. Eric recently took time out to discuss his upcoming book with EIN's Nigel Patterson. From Elvis in Memphis is due to be released in second half of 2020. ....The interview....

I’ve always loved history, so my love of Elvis led to a curiosity about the origins of rock and roll. My Mom worked for Faber & Faber (a UK-based publishing house), which published a book that changed my life: What Was the First Rock ‘n’ Roll Record? by Jim Dawson and Steve Propes. A chance trip to Memphis as a teenager solidified this interest, where I was surprised to find Sun Records a lot more fascinating than Graceland. This, combined with Peter Guralnick’s then-recent Last Train to Memphis, opened an entire world to me. I’ve been mapping it out ever since. EIN: How did your book From Elvis in Memphis come about as part of the Bloomsbury 33 1/3 series? EW: I stumbled upon the series a little over a decade ago (when it was still being published on Continuum), and was blown away. I emailed then-editor David Barker, pitching a book for Jerry Lee Lewis’s Live at the Star-Club, Hamburg. He told me that they weren’t taking new submissions at this point, but was supportive and told me to keep my eyes peeled for when they did. I loved the series, but was always surprised by the fact that there were no volumes about any of rock’s founders. The only rock artist active in the 1950s who had a volume was James Brown—Douglas Wolk’s Live at the Apollo, which for my money is the best book in the series—but Brown was most influential in the ’60s and ’70s. The fact there were no volumes about Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and Buddy Holly astounded me. There are so many great albums from the ’50s that rarely make those “Best Albums Ever” lists (or do but rank poorly)—Elvis’ self-titled debut, Here’s Little Richard, Chuck Berry Is on Top, The “Chirping” Crickets, etc. — I felt like the series was the perfect venue to try and rectify this. Over the next decade, I submitted proposals every time they had an open call, which was about every other year. I first wrote up a formal pitch for Live at the Star Club, Hamburg by Jerry Lee Lewis, but then shifted gears to Elvis Presley. I figured it was only a matter of time before Elvis got a volume, and I wanted to try to be the one who wrote it. Over the years, I wrote proposals for The Sun Sessions (the original 1976 LP), Elvis’s self-titled debut (twice—I submitted a revised version when a new team of editors took over the series), and The Complete Million Dollar Quartet (the 2006 50 th Anniversary reissue), before finally submitting From Elvis in Memphis this past October. I received word that my proposal had been selected in early January and signed the contract on Elvis’s birthday, January 8 th, of this year. Even though From Elvis in Memphis wasn’t a ’50s album, it was a ’50s artist. And for all those “Best Album Ever” lists that act like rock began with The Beatles, here was a masterpiece thrown right in the year of Abbey Road, Let It Bleed, The Band, Led Zeppelin II, Tommy, and countless other stalwarts of the rock canon. Plus, of course, it was Elvis.

EIN: Eric, what can readers expect in From Elvis in Memphis? EW: Readers can expect a cultural history of the album. As the 33 1/3 series has progressed, there has been a range of approaches. There have been historical accounts, but also more impressionistic pieces, partial memoirs, cultural analyses, and even a few novellas. Many of my favorite volumes—such as Douglas Wolk’s Live at the Apollo and Dan Le Roy’s Paul’s Boutique —function as sort of one-stop shops of everything you need to know about the album. This is similar of what I wanted to provide with From Elvis in Memphis. I largely structured the book to correlate with the album: The cover, the six songs on side one, the six songs on side two, and the back cover. Each chapter is a little under ten pages and generally mixes historical and cultural analysis. For me, writing about Elvis is a way of writing about music as well as writing about America. Elvis is inseparable from America in a way that I only believe is comparable to figures like Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln. But at the same time, the songs contain key themes of Elvis’s life, such as fame (“Long Black Limousine”), motherhood (“Only the Strong Survive”), poverty (“True Love Travels on a Gravel Road”), and more. In this regard, the album can be heard as a self-portrait —a portrait of the artist as a maturing American. EIN: The From Elvis in Memphis sessions are arguably Elvis’ most analysed. Without giving too much away, did you find there were new things to learn about them? EW: There were definitely new things to learn about them, thanks to two relatively recent sources. One source was Roben Jones’ loving and detailed history of American Sound, Memphis Boys: The Story of American Studios, from 2011, which is the definitive deep-dive into its subject, filled with new interviews of virtually every living person involved at the time of the writing. The fact that so many of these people have since passed away - Bobby Emmons in 2015, Chips Moman and Glen Spreen in 2016, Mike Leech in 2017, and Reggie Young in January of this year—makes this document all that more invaluable. The only principle musicians still alive today are pianist Bobby Wood and drummer Gene Chrisman. In 2012, Wood wrote his own autobiography, which was also useful, since he seems to be the musician who most bonded with Elvis during the sessions, while Chrisman has been interviewed extensively. By all accounts, both men are quite humble given their achievements. The other source was the Follow That Dream trilogy of Elvis’s American Sound sessions: Back in Memphis (2012), From Elvis in Memphis (2013), and Elvis at American Sound Studio (2013). These are the last word on these sessions, featuring masters, first takes, working takes, undubbed masters, and more. In many cases, every take of each song is included across the volumes. These albums allowed me to piece together the recording sessions in a way that was unimaginable even ten years ago. With American Sound Studio demolished thirty years ago and so many key players passed away—not only the ones listed above, but also Marty Lacker in 2017 and George Klein in February of this year, each of whom were key links between Elvis inner-circle and American Sound—the context of Jones’ book plus the fly-on-the-wall perspective of FTD’s anthologies allowed me to immerse myself in the album in an active way. Synthesizing this raw historical audio content with the various historical biographies (Peter Guralnick, Dave Marsh, Greil Marcus, Ernst Jorgensen, and Jerry Hopkins, among others) and memoirs (Wood, Lacker, Klein, and Priscilla Presley, among others) made me feel a little like the reporter at the center of Citizen Kane. When you have a subject as big yet elusive as Elvis, there are always new things to learn.

EIN: How important was Chips Moman to the finished album? EW: Chips Moman was crucial to the finished album. He had wanted to work with Elvis for years, and although he played it cool leading up to the sessions, he was clearly excited to work with Elvis and wanted things to run smoothly. What I hadn’t realized was that Elvis’s staff producer at RCA, Felton Jarvis (who died of a stroke at age 46 in 1981) was also on-hand as a producer — at least in name, as it appeared to several of the musicians at American Sound that his sole job was to keep Elvis happy. Chips, of course, had no inhibitions. And while he has the reputation of being a straight shooter to the point of curtness, when you listen to various takes of the songs, it is Chips’ voice that you most often hear, kindly encouraging Elvis to find new spaces in the sound that he otherwise might not have realized. The two songs from the albums that required the most takes—“Only the Strong Survive” and “In the Ghetto”—sound almost like a running conversation between Elvis and Chips. Peter Guralnick has a wonderful line in Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley where he says that Chips could play the studio—which, is to say, the musicians and singers—like it was one big instrument, which is such a great and accurate way to think about it. Chips was able to assemble musicians and make subtle suggestions that always shaped the whole into a sum that was greater than its parts. EIN: And how important were Mike Leech and Glen Spreen during the sessions? EW: I think they were both very important as the in-house arrangers for the strings overdubbed for the sessions. That said, these arrangements were overdubbed after the fact. Because of this, they were not at the active core of the recording sessions, which was my main focus for this book. One of the things I soon learned after completing my initial draft is that I had a lot more to say than the space I was allotted in the series. So Glen Spreen’s contributions are an avenue that I would have liked to explored more deeply in this book. I would like to say that Mike Leech is more central because by time of From Elvis in Memphis, he was the in-house bassist since Tommy Cogbill had taken on more of a leadership role in the studio of bandleader and assistant producer (although both Leech and Cogbill are frustratingly listed as bass players in the sessions). However, Leech had a cancer scare after the first round of sessions in January, which meant he was completely absent from the February sessions, where Cogbill stepped in. Leech had a very organic, driving bass style that dug into the earth (check out “Suspicious Minds”), while Cogbill was a chameleon who could play all around a song like a sixth sense (check out Dusty Springfield’s “Son of a Preacher Man”).

That said, Cogbill could play in a style like Leech’s and there’s more than one song from the January sessions that sounds to me more like Cogbill than Leech. Sadly, Cogbill died of a stroke at age 50 in 1982, and as far as I can tell, he never sat down for an interview. All of which is to say that although Leech was the other on-hand arranger, I focused on his bass work pretty much exclusively. I am also not exactly sure when he came back into the fold at American following his cancer scare. Another reason why I didn’t focus on the string sections is because I was always surprised how full the songs sounded with just the five Memphis Boys and Elvis. Even places where I thought the backing vocalists—mostly Mary “Jeannie” Green, Donna Thatcher, Ginger Holladay, Mary Holladay, and Susan Pilkington (all of whom are still alive and I plan to reach out to)—must have been reacting live to Elvis and the band and vice-versa, were seemingly overdubbed after the fact. This is another area I would have liked to visit in more depth, because you feel their presence just as strongly as the strings and horns. As long as you listen to the undubbed masters and working takes in stereo, you will hear that in nearly every one, all of the instruments are in the left channel except for the bass, which is by itself in the right (Elvis’s vocal is in both channels). It is thus the right channel that often gets a lot of the overdubs—strings and horns, but also additional organ and guitar, depending on the song. I think this isolation of the bass was part of how these songs had such a hard groove. Perhaps it’s a bit like when John Lennon went to George Martin in 1966 and asked why their records didn’t sound like Wilson Pickett, and you can basically hear the bass boosted in The Beatles’ sound overnight. And guess who was the bass player in many of those classic early Wilson Pickett records? None other than Tommy Cogbill. EIN: That is interesting. EIN: Elvis was effectively producer for many of his recordings. However, in the case of his strongest output, his Sun recordings and the From Elvis in Memphis tracks, there was a strong producer controlling the recording process and final product. This seems to beg the question…what can we take from this?

Elvis with producer Chips Moman

EW: I think this is proof that Elvis (and perhaps any artist) can only take themselves so far. Elvis needed Sam Phillips to guide him at Sun just like he needed Chips Moman to guide him at American Sound. They were able to see a fuller picture than Elvis that spoke to where he fit into the greater impact of the sound. This is not a slight on Elvis. If anything, it speaks to the level of openness and collaborative creativity he was able to provide at different stages of his long and varied career. Another version of this that I thought a lot about was the correlation between Elvis’s greatest recorded moments - which I count as Sun (1954-55), pre-Army RCA (1956-1957), post-Army RCA (1960 Elvis Is Back! sessions), the “sit-down” shows of “The ’68 Comeback” special (1968), and American Sound recordings (1969) - and Elvis working with a tight band - first “The Blue Moon Boys,” then the 1960 studio men, then his friends in 1968, and finally The Memphis Boys. Each period yielded anywhere from 18 to 40 songs or so that were insanely consistent and masterful. As much as Elvis gets credit as a solo act (and deservedly so), in order to play rock and roll, you need a full band. And it seems virtually every time Elvis hit a gold streak, it was with a tight-knit group of musicians. And while the role of the producer definitely helped to shape both Sun and From Elvis in Memphis, I would also like to posit that another common denominator is Memphis. Although Elvis didn’t move to Memphis until he was 13, it is where he came into his own, and his once and forever home. There is something to be said for the high quality of these Memphis-based sessions, like there was something in the water. That said, this isn’t a strict rule because Elvis’s other two Memphis-based sessions — at Stax in 1973 and in the Jungle Room in 1976—which, while quite underrated in my opinion (especially his December sessions at Stax), are admittedly less successful. However, in both of these later cases, he recorded in Memphis largely out of laziness, as opposed to Sun and American Sound, where he actively pursued the studio. So there needs to be a level of engagement there—Elvis had to be able to meet the sessions halfway. I think what we can ultimately take from this is that recording great music should be seen through a wider scope than is usually utilized. Especially in the post-Beatles era, people think of an artist or band as a self-contained unit, which is sometimes true, but more often an oversimplification. The Beatles wouldn’t have been The Beatles without George Martin just like David Bowie wouldn’t have been David Bowie without Tony Visconti. Or Michael Jackson wouldn’t have been Michael Jackson without Quincy Jones. The list goes on and on. Because the role of the producer can be so varied from style to style (with Phil Spector on one end of the spectrum and Andy Warhol on the other), people often overlook their importance because it’s so hard to pinpoint. This is exactly why producers like Sam Phillips and Chips Moman are so important. They set the scene, serving almost more as a dinner party host than as a professional working in the music industry.

EIN: Eric, what is your view on why Elvis never returned to record at American Sound Studio? EW: This is one of the great mysteries (and frustrations) of this period. Elvis recorded 32 masters in a little under two weeks, which is arguably his most prolific period ever. And many of those songs are classics—four of which (a full 12.5%!) were Top 20 hits—that make up a central part of his legend. So why did he never return? I was hoping to get a definitive answer to this riddle, but if it’s out there, it has eluded me. As is almost always the case, the reality of the situation is more complex than meets the eye. I’ve heard a bunch of different theories as to why Elvis never returned, with varying levels of bad blood. Among them are: The Colonel’s Own Ideas: Sources indicate that the Colonel was more than a bit skeptical about Elvis recording at American Sound, which had far more variables than the traditional sterile RCA session. For the second time in two years (the first being “The ’68 Comeback Special” not being a tux-and-tails family Christmas show), the Colonel basically said, “Good luck, sucker” to Elvis, only to be proven spectacularly wrong. If Elvis could collaborate so well with Steve Binder on the TV special and Chips Moman on the recording sessions, who’s to say that Elvis wasn’t smart enough to realize that maybe he didn’t need to be under the Colonel’s thumb after all? The Colonel hence poisoned the well with bad intel about Chips and his studio and/or simply circumvented any chance for Elvis to return. Elvis’s Own Ideas: Regardless of whether the Colonel contributed to Elvis’s feelings about Chips and American Sound, and by 1970, he clearly had his own opinions. Marty Lacker remembers suggesting to Elvis that he return to American Sound in 1970 for his next sessions, which made Elvis launch into a tirade against Chips. Lacker stood up for the producer, trying to explain to Elvis where he had misunderstood things. Elvis heard him out, but ended up by declaring, “Regardless, I ain’t goin’ back to that studio again.” Chips’ Own Ideas: Recording Elvis meant that Chips had to relinquish an unusual amount of control for his home team. On the final version of From Elvis in Memphis, there are no credits on the back of the album, and the only place where you can find someone’s name besides Elvis is the songwriting copyright notices on the disc itself. There’s no mention of Chips, any of The Memphis Boys, engineers, backing singers, arrangers, string musicians, horn musicians, or backing singers. In fact, there is no mention of American Sound Studio. The only way to know where it was made was to see the tip-off “Memphis” in the title and let the inimitable music speak for itself. Over the course of the recording and release of the sessions, Chips locked horns with RCA brass over many issues, such as songwriting royalties on “Suspicious Minds” as well as producer credits on the “In the Ghetto” single. Some of these he won and others he lost, but it must have been a final insult to have his studio remain completely anonymous on the final project. All of which is to say that maybe Chips simply didn’t want to deal with this stuff again. In truth, I believe that more or less all of the above is true. It was overlapping and interconnected frustrations of three men — the Colonel, Elvis, and Chips — who each had a strong enough personality to prevent a collaboration like this to happen again. I personally think Elvis may have had his own suspicions and frustrations, which were exasperated by the Colonel’s hidden agenda and Chips’s own wariness. Two last telling pieces that I believe helped seal Elvis never returning to American Sound: (1) Elvis initially asked The Memphis Boys to back him for his Vegas shows (they said no, they could get more money doing studio work) and (2) the way that RCA manipulated the “Suspicious Minds” single so that it was extended with the fade and horns to mirror Elvis’s live versions (which led Chips and his crew feeling varying levels of shock and distain). The Memphis Boys didn’t want to be Elvis’s anonymous backing band and they had no patience for his label tampering with their art. In hindsight, it seems that RCA simply represented the big corporate machine of the music business that Chips spent his whole life resisting and rebelling against.

EIN: Eric, it has been reported that by the late 60s-early 70s, Elvis expressed concern that his recordings did not sound like/were not as sophisticated as those produced by other major recording artists. Do you think Elvis’ recordings could have benefitted from more contemporary production arrangements (e.g. multi-tracking, better overdubbing, use of feedback, tape manipulation, etc)? EW: I think that Elvis’s recordings definitely could have benefited from

more contemporary production elements. It’s tempting to wonder what

Elvis could have done with what would have been then state-of-the-art

equipment, but the fact the Beatles were able to do so much with so

little working with the relatively modest equipment at Abbey Road speaks

to the fact that there must be a sort of intellectual curiosity on the

part of the artists, musicians, and producers. By the mid-’60s, so much

of Elvis’s output were those generic film soundtracks where the focus

seemed to be most on getting Elvis’s vocal out there, and not so much on

the overall production values. For them, like so many other musicians and fans, Elvis was more than just a performer. He was a way back home.

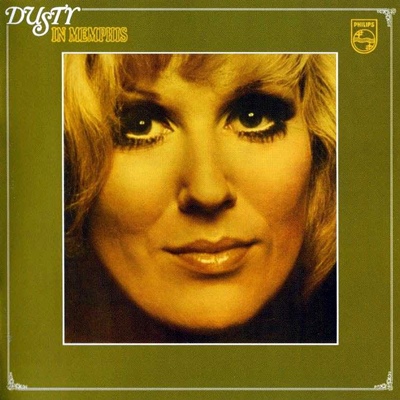

EIN: In November 1968, Dusty Springfield also recorded a seminal album (Dusty in Memphis) at American Sound Studio. What was it about the American Sound Studio that, like Sun Studio in the 1950s, such incredible music was being recorded there in the late ’60s-early ’70s? EW: I’ve come to believe that the key was they used live musicians so that the recordings were built around an essentially live-in-the-studio sound. In Ian MacDonald’s masterful treatise on The Beatles, Revolution in the Head, he argues that the ’60s produced so much special music because it was before people started overdubbing their parts into a soulless sound. He said that there was space in the recordings — which is to say, musicians reacting to each other in ways that were not planned, let alone even conscious. This allowed for room in the sound that could never be achieved by stacking tracks recorded in isolation. Yes, the sound of the latter would be more perfect, but great rock and roll is not about perfection. It needs to breathe. I believe that all of the classic “hubs” of rock music — Sun Records, Chess Records, Motown Records, The Beatles’ initial catalog, Bob Dylan’s first electric sessions, etc.— all achieved their most classic hits by the fact they was recorded live in the studio. Additionally, so many classic one-off singles from Bill Haley and His Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” to The Five Satins’ “In the Still of the Night” and The Kingsmen’s “Louie, Louie” were recorded the same way. And American Sound was part of this tradition. By the late ’60s, this was already becoming an archaic way to record, but they wisely stuck by it. Before Elvis recorded at American, he had been churning movie songs with pre-recorded tracks. At American, Chips had the band cut the takes live in the studio with the singer (in this case, Elvis) at the center; it is written that the vocal would then be overdubbed, but at least for the case of Elvis, it appears that it was more touch-ups and corrections than full re-dos. Thus, lion’s share of the work was already done by the time they had reached the master takes. Like the house bands at Motown and Stax, The Memphis Boys were like brothers of the same mind, able to interact with each other on a level that most groups cannot even conceive. They were also simply masters at their instruments. For all the times that a take was called short in Elvis’s sessions at American Sound, I cannot think of a single time it was because of one of The Memphis Boys playing a wrong note. They were all because of Elvis screwing up, or occasionally, Chips messing up something from his end, or suggesting a slightly different approach—such as a change in tempo or the way a part is played—that wasn’t to correct a mistake, but rather to shift the feel of the recording. The fact that Chips insisted on capturing this live and in-the-moment helped to give it a singular power, the way little music has had before or since.

EIN: American Sound Studio only existed for less than nine years. What was it that led to its demise after producing such great music? EW: This is somewhat outside of the scope of my project, so I feel like I’d need to do more homework before I could really answer it. But that said, one thing that struck me about American Sound that set it apart from the other places in town it is usually compared to—Sun, Hi, and Stax in town and places like Motown outside of town—it was never a record label, only a recording studio. I feel like this element is often forgotten when people think of American Sound (or don’t, as the case may be). Places like Sun and Stax could craft their own sound and sell it through records, whereas American Sound played a slightly different role: It was a place where you went to record a record, not release one. As a result, there were always people coming through and using the sound for their own purposes. That, combined with a lack of ego on Chips Moman’s part, seems to be what did the studio in. Since they didn’t have a record label to attach to their sound (like Sun and Stax did), there wasn’t a brand that could be associated with the buying market. When stuff began winding down in the early ’70s—and the same was true all around town in Memphis, as Sun essentially had ceased to exist and Stax only had a few years left—Chips got out rather than sit around catering to diminishing returns. His restlessness prevailed as he first set up shop in Atlanta, then Nashville, and even back to Memphis, but he never equaled the heights of the golden age of American Sound. And yet, what does that even mean? American Sound is a bit of a double-edged sword. On one had, they did have enough of a sound that people sought them out (like Elvis) to try their luck with the studio’s golden touch; but on the other hand, the musicians were so incredibly versatile that they could record soulful music with groups as diverse as The Box Tops, Merrilee Rush, Neil Diamond, Dusty Springfield, and, of course, Elvis. Hence, there is a paradox: American Sound was at once a group with a singular sound yet they could also fit that sound to work with anybody. So while the Sun sound defined rockabilly and the Stax sound defined funk, American Sound simply provided first-rate pop. In many ways, that’s the hardest thing to achieve, but with no label or roster of artists to define them, it was that much harder to carve out an identity. Places like Sun and Stax often got more attention because people already had a working idea of what they were all about. American Sound did not have it so easy. Sadly, this contributes to their underappreciated state today. It is a travesty that none of The Memphis Boys—up through and including Chips Moman and Tommy Cogbill—are in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. If my book does nothing else but shine a light on these men and their contributions to rock music, it will all have been worthwhile. EIN: When will From Elvis in Memphis be released? EW: There is still a lot of editing to be done so a firm date has not yet been set. At this time it is likely to be mid 2020. I will let EIN know when a firm date is known. EIN: Eric, thank you very much for telling us about From Elvis in Memphis. We know that many fans are looking forward to its release.

|

|