|

|

The Politics of Saving the King’s Court: Why We Should Take Elvis Fans Seriously. (excerpts from an academic treatise by Derek H. Alderman, University of Tennessee)

EIN introductory comment: In what is a wonderful example of people power, this article highlights “how” Elvis fans united to successfully prevent the demolition of the Lauderdale Courts in 1995…..a proposed demolition which, at the time, was supported by EPE!

Background: In 1995, the Memphis Housing Authority proposed to raze Lauderdale Courts, a downtown housing project, as part of a larger “dedensification” program led by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD’s vision of reforming substandard, crime ridden public housing apartments through demolition had drawn criticism from politicians and activists across the country who claimed the reform would bring a sharp drop in the number of housing units available for very poor families and render many people homeless.

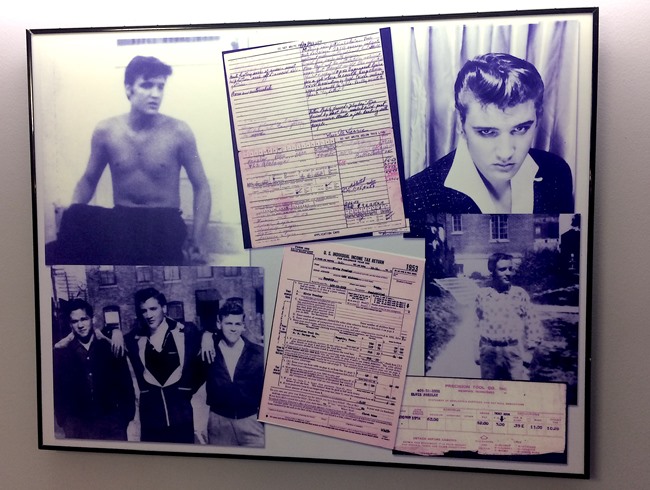

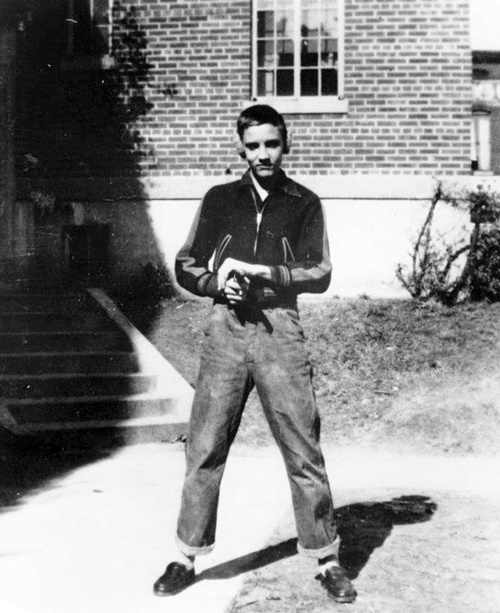

The tearing down of Lauderdale Courts (also known by locals as “the Courts”) proved particularly contentious, but for different reasons. Historic preservationists pointed out that the Courts, built in 1938 under the auspices of the New Deal, was one of the country’s first federal housing projects. What drew even greater attention, however, was the fact that a teenage Elvis Presley and his parents had lived at Lauderdale Courts from 1949 to 1953, specifically 185 Winchester Avenue, apartment 328.

Elvis fans unite to prevent demolition of “the Courts”: Learning of these plans to demolish the Presley apartment, Elvis fans worked successfully with journalists, historic preservations, city officials, and area developers to save Lauderdale Courts. Fans argued that the Courts provided a view of Elvis’s humble beginnings not available at the opulent Graceland estate. Moreover, the apartment building had been an important transitional site in the King’s personal and musical development. Elvis signed his first record contract with RCA just a little over two years after leaving Lauderdale Courts. As Judith Johnson, a Memphis preservationist, asserted: “This [Lauderdale Courts] is Elvis Presley’s life .... It’s on a very human scale. Everything that influenced him is in a four-block area from his apartment building, and this is the last place where he was normal.”

Opposition to the saving of Lauderdale Courts came from all quarters, even among Elvis advocates. When razing the Presley apartment was first proposed, the management of Graceland and even some Elvis fans supported the demolition plan.

Of the many people involved in the preservation struggle, three Memphis-based Elvis fans – Mike Freeman, Cindy Hazen, and Georgia Anna King – played a noteworthy role. Freeman and Hazen gave tours of the threatened apartment building to visitors and articulated a convincing narrative of the historical importance of the Courts. Along with Georgia King, they formed strong political coalitions with local historical preservationists, who helped place the structure on the National Register of Historic Places.

King, in particular, used her organizational experience and connections as a neighborhood activist to bring legitimacy to the cause of saving the Elvis apartment. In addition, her identity as an African American lent added credibility to the campaign, defusing suggestions made by opponents that the preservation struggle was carried out by white Elvis fans out of touch with the housing needs of poor black residents. While Freeman, Hazen, and King took advantage of their local influence and resources, they also mobilized the geographically expansive community of fans that communicate with each other about Elvis-related events and causes.

Georgia King, who at the time was President of the Elvis Presley International Fan Club Worldwide, organized a major petition drive. Using book and Internet publishing, Freeman and Hazen asked fans across the United States and the world to write letters of protest to a host of authorities, including the HUD office in Washington, D.C. By involving this wide fan base in the Lauderdale Courts campaign, Freeman, Hazen, and King broadened the scale and cultural importance of their struggle.

Lauderdale Courts has since been renovated and renamed “Uptown Square” as part of a larger Uptown Memphis revitalization initiative. Completed in 2004 after spending $36 million in private and public funds, Uptown Square is a mixed-income apartment community with some units reserved for public housing residents and the remainder rented at market rate to young professionals. Even after it was clear that the Presley apartment would be saved, Elvis fans continued to influence the redevelopment project.

Uptown developers Henry Turley and Jack Belz solicited ideas from fans and the general public on how best to use the famous apartment. They received hundreds of responses and it was eventually decided that the apartment would be renovated to look like it may have appeared when the Presleys lived there, even down to period furniture and household items. During two weeks of the year when the largest number of Elvis fans are in Memphis (the Birthday Week in January and Elvis Week in August), the public is allowed to tour the apartment. The rest of the year, the apartment can be rented out to fans or curious observers for about $250 a night. - (see Exclusive EIN Report: A Night in the Presley Family Apartment)

In trying to save the housing project, Mike Freeman, Cindy Hazen, and Georgia King actively reconstructed the scale of their reputational struggle, seeking to convince critics of Elvis’s importance by showing them that a vast, global fan base was concerned about the fate of Lauderdale Courts. King collected at least a thousand signatures of Elvis fans in support of saving the Courts.

Freeman and Hazen used two primary media conduits for mobilizing support: the World Wide Web and book publishing. Throughout the struggle to save Elvis’s apartment, Freeman and Hazen maintained an advocacy web page. The page, linked with numerous other Elvis fan sites, instructed Internet users in what they could do to save Lauderdale Courts. For instance, visitors to the site were encouraged to ask reporters at their local newspapers to cover the preservation struggle.

In an effort to attract sympathy from influential figures living beyond Memphis, Freeman and Hazen asked web surfers to seek out famous people who would write letters of support. Noted authors, academicians, and artists responded, including southern folklorist and former NEH Director William Ferris.

More importantly, however, the Lauderdale web site provided the mailing addresses of several government offices and politicians and strongly directed people to write the key decision-making agency, HUD. Ideally, these letters would convince HUD – which initially argued that the demolition of Lauderdale Courts was purely a local decision – of the national and even international importance of preserving the Elvis apartment.

As mentioned earlier, a similar call for letters of protest was included in the book written by Freeman and Hazen, Memphis: Elvis-Style. In early releases of the book, the authors went as far as providing buyers of the book with postcards that could be mailed to then-Secretary of HUD, Andrew Cuomo, in support of saving Lauderdale Courts. Each card provided a place for the sender’s name and address, thus providing a rich data source for estimating the geographic scale of support mobilized around this commemorative issue.

In asserting that the Elvis apartment was worthy of being saved as an important landmark and place of pilgrimage, fans engaged in a “reputational politics” as they sought to convince the wider public of the legitimacy of their idol’s commemorative legacy. The historical reputation of a person – whether it is Abraham Lincoln or Elvis Presley – is not simply made by the individual in question but written and rewritten by social actors and groups, who seek to advance their own commemorative agenda and divert the agendas of other parties.

Social mobility was an important part of the historical narrative that Hazen and Freeman attempted to build around Elvis’s connection with Lauderdale Courts. Elvis is often represented as the embodiment of the “American Dream” mythology. Fans embrace him as someone who made tremendous gains in wealth and status without forgetting his working-class roots.

Part of the narrative clarity of the campaign to save the Elvis apartment came from the way in which Freeman, Hazen, and King dealt with opponents to their cause. Freeman and Hazen wrote editorial letters that took aim at the Memphis Housing Authority, arguing that the agency had “failed to maintain its apartments within reasonable living standards while spending large sums of money,” which led to the poor living conditions in Lauderdale Courts.

Georgia King took on housing officials on numerous occasions, including a heated, closed-door meeting with national and local government officials. By virtue of her identity, she proved particularly effective in defusing the Housing Authority’s counter narrative that the campaign to save Lauderdale Courts was led by fans insensitive to the housing needs of the poor. A long-time advocate for the homeless in Memphis, King received a Women of Achievement Award in 1994 in recognition of her community activism. She was cited for her courage, especially her efforts to open a mission for the homeless on South Main and her over 250-mile walk from Roanoke, Virginia to Washington, D.C. to bring the plight of the homeless to the attention of Congress.

In conclusion, the Lauderdale Courts controversy is an important moment in the study of Elvis and the modern American South. Elvis culture, like southern culture, is not a fixed entity but a collection of fluid exchanges that circulate or “circle” across different countries and continents. Fans play an important role in the constant reconstruction and recirculation of Elvis’s memory. They function as commemorative activists and show a commitment not only to protecting Elvis’s legacy but also to preserving the places connected with that legacy.

In this respect, fans are geographic agents, helping shape the form and meaning of the Elvis-related landscape while also shaping their idol’s historical reputation. Recognizing this connection with geography is essential to understand the larger cultural importance of Elvis fans as a legitimate social and cultural movement.

The politics of saving the King’s Court is, of course, a lesson in the reputational power of Elvis as a cultural icon. But, perhaps more importantly, it is also a lesson in the reputation of Elvis fans and the need to address the serious role they play in society and their potential to operate as an interconnected, politically active community of memory.

To read the full text of Derek Alderman’s thought provoking and fascinating treatise: Academia.edu

(Spotlight, Source: Academia.edu)

Go here to Lauderdale Courts Elvis Facebook page for more

|

|