|

|

Big Boss Man: What Kind of Technical Advice Did Parker Provide for Elvis’s Movies? Although many aspects of Presley’s life are still a matter of fierce debate, there is no doubt that Parker orchestrated the star’s move to Hollywood, negotiated all the movie contracts on his client’s behalf with input from the William Morris agency, and expressed the view that "all Elvis’s films are good for is making money." As the easiest way to make money was to sell music, Presley would sing in thirty of his thirty-one feature films.

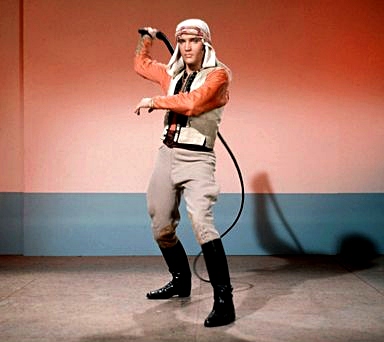

The Colonel developed the strategy – and ensured it was executed. Though his client often complained that he was "tired of these damn movies" in which fought in one scene and sang to a dog in the next, he never decisively rebelled, signifying his distaste by hiding in Memphis for as long as possible until the next shooting schedule beckoned. Presley proved especially reluctant to turn up for the making of Harum Scarum and Clambake, infuriating his manager. Yet Presley was usually, as Hoey has noted, "very conscientious about his work, and always arrived on the set on time, knowing his dialogue and ready for business." Parker had repeatedly threatened Elvis that if he offended the studios he would return to oblivion, cleverly exploiting one of the star’s recurring nightmares. It is much harder to say with clarity how much interest Parker took in the movies themselves. Hoey said: "The Colonel had absolutely no interest in the quality of the projects, only the size of the check. His only consideration was with the music selection and a quick read of the script to see where the songs would fit." Once, when Hoey and Taurog discussed a different kind of film role, Elvis urged them to consult his manager. Parker refused to read the script, saying, "Give me a million dollars and you can have him and shoot the phone book, if you’re crazy enough." Elvis’s manager certainly liked to suggest that he only cared about money, telling Variety in 1964: "Look, you got a product, you sell it. As long as the studios come up with the loot, we’ll make the deal." Michael Fessier Jr., who interviewed Parker for Variety, explicitly points out in the story: "Once a deal is made, the studio takes complete control of a film, the Presley camp having no say-so on cast, script or production costs." Parker justified this laissez-faire attitude, saying, "We start telling people what to do and they blame us if the picture doesn’t go. As it is, we both take bows and if it doesn’t hit, maybe they get more blame than us. We don’t have approval on scripts – only money. Anyway, what’s Elvis need? A couple of songs, a little story and some nice people with him." As usual with the Colonel, the reality was nowhere near as straightforward as his observations suggest. For a start, there were rarely just a "couple of songs". Only seven – Change of Habit; Charro!; Flaming Star; Live a Little, Love a Little; Love Me Tender; Stay Away, Joe and Wild in the Country – had fewer than five numbers. In his memoirs, Elvis, Sherlock and Me, Hoey says Parker and Presley both had a say in the soundtrack selection: "Their choices differed greatly and the Colonel, looking out for his album tie-ins, frequently prevailed." The Variety interview fails to reflect how Parker’s contractual shenanigans shaped how and what films were made. For a start, his insistence on a large fee upfront for his "boy" made it significantly less likely that a studio would take creative risks. Parker acknowledged as much, telling Variety he had turned down one producer who had asked to reduce Elvis’s fee so he could pay for a better script and rebuffed another who insisted he had an Oscar-winning story: "I told him pay us our regular fee and if Elvis gets the Oscar, we’ll give his money back. We never saw him again."

While Presley dreamed of an Oscar nod – not an absurd aspiration after King Creole and Flaming Star – Parker pursued a very different holy grail: getting a fee of $1m a picture for his star. He achieved this milestone – or millstone – in 1966, just as the musical comedy travelogue formula was wearing thin. He was perplexed when Elvis, who understood the impact this would have on budgets and co-stars, greeted his new status as Hollywood’s highest-paid star rather coolly. Needing to recoup such hefty fees, the studios usually played safe, giving the audience more of what the box-office receipts had proved they wanted in the past.

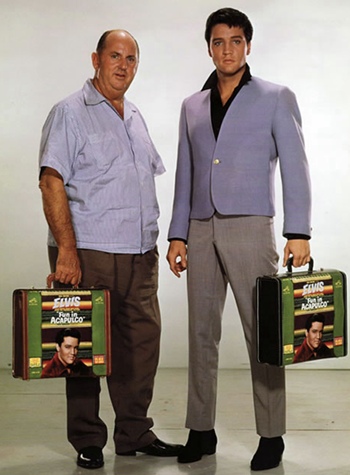

The star’s fees forced producers to cut costs, although even Parker, after watching Harum Scarum and complaining it would take a "55th cousin of P. T. Barnum" to sell the movie, decided never to work with quickie producer Sam Katzman again and wrote to MGM suggesting they spend more time on the next film to improve quality. By then, with box-office revenues shrinking, the studios were more interested in trimming budgets. Though Hoey insists the Colonel never had any input into the screenplays for the movies he worked on, Parker didn’t always just stand idly by, counting the money, devising promotional stunts, and suggesting movie titles. (Clambake was his idea. He also helped persuade MGM to retitle Chautaqua as The Trouble with Girls (and How to Get Into It). Right from their first meeting in 1956, Hal Wallis and his partner Joseph H. Hazen had known Parker would need careful management. Making Roustabout (1964) was partly designed to flatter the Colonel, honoring his carnival past, a point Wallis made explicit in a letter: "Of course, we want you to be associated with the project, as I know how close this type of life is to you." This wasn’t mere rhetoric: the producer paid Parker $25,000 for a weekend’s consulting on carny lore with scriptwriter Allan Weiss. The notes from that meeting are detailed and specific, and three of the manager’s suggestions made it into the final film. Parker didn’t look at some scripts, telling Katzman it would cost $10,000 to appraise a draft for Kissin’ Cousins, but did read others, notably those for Spinout and Kid Galahad. Co-writer Theodore J. Flicker once recalled the making of Spinout: "Pasternak had given us the line for the story: the daughter of the richest man in the world wants her father to invite the biggest singing star in the country to sing for her Sweet Sixteen Party. So we sat down, we tried to imagine what Elvis’ life was like. And we wrote that – as if we were writing a real movie. The next thing we knew, the head of the studio called us in and said: ‘The Colonel read the script and said ‘When I want to do Elvis’ life story, I’ll get a hell of a lot more than a million dollars for it.’" A new script was submitted, and Parker turned up in the writers’ offices, threw the script on the desk, and said: "This is great. Just one thing: put a dog in it."

A senior suit at MGM then told Flicker and co-writer George Kirgo, "We can’t accept this script. There’s no racing in it." Having added a dog, they were hardly likely to balk at incorporating racing cars, in the vain hope of repeating the box-office success of Viva Las Vegas. All the revisions were complete when Elvis turned up at MGM for pre-production in February 1966. Spinout was not the only significant departure from Parker’s official policy of non-interference. John Flynn, assistant director on Kid Galahad, told Bill Bram, author of Elvis Frame by Frame: "The writer asked: ‘Colonel, how did you like the script?’ The writer was wondering how the Colonel liked the dramatic flow but the Colonel couldn’t give a shit. He just said ‘It needs two more songs.’" When the writer queried this, the Colonel explained: "Boy, there’s ten songs on an album and you got eight. It needs two more songs." In the event, the released version contained six songs, but here, once again, Parker made his point, sending out a message not just to the makers of that film but to the producers of other Presley pictures. The bowdlerization of the script for Charro! – a much raunchier, tougher spaghetti Western in its initial incarnation – into something that felt more like an extended episode of Bonanza also smacks of Parker’s concern to maintain his star’s all-round family entertainer image. Before the release of That’s the Way It Is in 1970, the Colonel detailed his objections to certain scenes in a three-page letter to MGM boss Jim Aubrey. Needless to say, his concerns were all addressed. The idea that Parker didn’t approve anything in Elvis’s films but the money was a convenient fiction and, like many great fictions, all the more convincing because it contained some truth. The Colonel was obsessed by money, but he also kept close, almost claustrophobic, tabs on Presley, monitoring shooting, dropping in to offer his own brand of comic relief when nerves got frayed (striding around the set of Kissin’ Cousins wearing Elvis’s blond wig), and stopping the cameras rolling one morning on The Trouble with Girls set because Presley’s eyes were puffy. He was also the conduit for producers’ instructions regarding his star’s appearance – Wallis was particularly critical about Elvis’s weight, facial appearance, and hair as the 1960s wore on.

The Colonel’s influence on casting is hard to gauge. Marlyn Mason, Elvis’s leading lady in The Trouble with Girls, was chosen over his objections. Parker, the actress recalled, "wanted some buxom blonde; and Peter Tewksbury said ‘I’ll walk if you don’t cast Marlyn.’" It sounds plausible, although there’s little other evidence of Parker trying to have his say on casting, apart, perhaps, from noting that Elvis enjoyed working with particular actors, such as Shelley Fabares.

The clinching evidence that Parker did not hand over complete control to the studios during filming is provided by Viva Las Vegas. Realizing the production was busting its budget – and that Ann-Margret was getting as much of the limelight as Elvis – he protested so vehemently that the stars’ duet on "You’re the Boss" was cut. Complaining that director George Sidney’s camera angles favored Ann-Margret, he threatened to drop his usual promotional campaign. Though he couldn’t stop the cost overrun, Parker won most of the other battles and, enraged, made the disastrous decision to make two pictures with penny-pinching Katzman. Ironically, Viva Las Vegas is one of nine Presley movies in which the Colonel is not credited as technical advisor. The relationship between Presley and Parker remains so mysterious as to be all but unfathomable. The most likely explanation for the Colonel’s dominance – that, offstage, Presley lacked the confidence to confront such a powerful character and was doubly reluctant to do so because of his morbid fear that he would slip back into the poverty of his youth – is too prosaic for many, who prefer to speculate about blackmail and other dark arts. Depending on whom you believe, Parker may have threatened to reveal the family’s guilty secret (Vernon Presley’s conviction for fraud), compromising photographs of the star, or the terrible details of a youthful stunt involving three midgets, a human cannonball, and the roof of Ellis Auditorium in Memphis. Others – notably Steve Binder, the producer of the 1968 TV special, have a simpler explanation: "I swear the Colonel hypnotized Elvis."

Parker’s flamboyance was eye-catching, a useful sleight of hand to obscure the fact that some of his more ruthless practices weren’t that dissimilar from the mob’s. This chilling account, by Presley’s friend Arlene Cogan, of Parker’s visits to Graceland, partly explains why the singer feared his manager: "The Colonel would just take over the house. He would bring in some of his men and they would screen the telephone calls. Vernon told us that when Parker came to the house and got Elvis locked up for a meeting, he couldn’t even talk to his own son till Parker left."

After Presley’s death, Parker declared: "Yes, I did love him" – an enigmatic statement that tacitly admitted the issue was, publicly at least, in doubt. Yet love is too simple a word for what Parker felt for Presley. There was plenty of resentment, obsession, jealousy and anguish in there too. Raphael recalls Parker’s reaction when Elvis forgot his birthday on June 26, 1957. After a birthday bash, Raphael stayed at the Parkers and was woken by, as he told Nash: "These horrible sounds . . . like an animal wailing, the strangest sound I ever heard in my life." The crying lasted all night long and when the aide raised the issue with Parker’s wife Marie, she shrugged: "Oh I don’t know, Elvis forgot the Colonel’s birthday." Stunned by the reaction to such an oversight, Raphael quickly got word to Elvis, who gave him a ring and instructions to say he just hadn’t been able to deliver a gift in time. Parker wasn’t deceived. Whatever kind of technical advice Parker provided for Presley’s movies, he was hardly a disinterested professional. Maybe the answer to the mystery of how rock’s most charismatic star came to sleepwalk his way through such fluff as Paradise, Hawaiian Style lies in his extraordinarily opaque and complex relationship with his controversial, manager.

EIN Website content © Copyright the Elvis Information Network.

Elvis Presley, Elvis and Graceland are trademarks of Elvis Presley Enterprises. The Elvis Information Network has been running since 1986 and is an EPE officially recognised Elvis fan club.

|

|